The reporter sat down on a rock without saying a word.

After the raft of wood was unloaded Pencroff’s first concern was to make the Chimneys habitable by obstructing those passages through which the wind blew. Some sand, stones, intertwined branches and mud hermetically sealed the corridors of the “&c” which were open to the winds from the south, thus isolating the upper loop. One passageway only, narrow and winding, opening on one side, was kept in order to conduct the smoke outside and to induce a draft from the fireplace. The Chimneys were thus divided into three or four rooms, if one could give this name to such gloomy dens with which a wild beast would hardly be content. But it was dry and one could stand up, at least in the main room which occupied the center. A fine sand covered the ground and everything taken into account, they would have to manage until they could find something better.

While working Herbert and Pencroff chatted.

“Perhaps,” said Herbert, “our companions have found a better accommodation than ours?”

“That is possible,” replied the sailor, “but doubtful, so don’t hold your breath! It is better to have one string too many in your bow than no string at all!”

“Ah!” repeated Herbert, “if they could only bring back Mr. Smith when they return, how we would thank Heaven!”

“Yes,” murmured Pencroff. “That was truly a man!”

“Was...” said Herbert. “Do you despair of ever seeing him again?”

“God forbid!” replied the sailor.

The arrangements were quickly completed and Pencroff was quite satisfied with them.

“Now,” he said, “our friends can return. They will find a suitable shelter.”

It remained to build a fireplace and to prepare a meal, really a simple and easy task. Some large flat stones were placed on the ground in the first corridor on the left at the entrance of the narrow passageway which had been reserved for this purpose. If the smoke did not draw out too much heat this would evidently be sufficient to maintain a proper temperature inside. A load of wood was stored in one of the rooms and the sailor placed several logs and small pieces of wood on the rocks of the fireplace. The sailor was engaged in this work when Herbert asked him if he had any matches.

“Certainly,” replied Pencroff, “and I will add, fortunately, because without matches or tinder we would have quite a problem!”

“We could always make fire the way the savages do,” replied Herbert, “by rubbing two pieces of dry wood against each other.”

“Well, my boy, try it and then see if you can find a better way to break your arms.”

“Nevertheless it is a very simple procedure and is often used on the islands of the Pacific.”

“I do not say no,” replied Pencroff, “but I believe that the savages know just how to do it or that they use a particular wood because more than once I have tried to make a fire in this way and I have never succeeded at it. I admit that I much prefer matches. By the way, where are my matches?”

Pencroff searched in his vest for the match box that was always with him because he was a confirmed smoker. He did not find it. He rummaged through his pants pockets and to his amazement he could not find the box in question.

“This is stupid! It’s more than stupid!” he said looking at Herbert. “This box must have fallen out of my pocket and I have lost it! But you, Herbert, do you have a tinder box or anything that we can use to make a fire?”

“No, Pencroff.”

The sailor went out scratching his forehead followed by the young boy.

Both searched with the greatest care on the beach, among the rocks, near the bank of the river, but to no avail. The box was made of copper and should not have escaped their attention.

“Pencroff,” asked Herbert, “didn’t you throw the box out of the basket?”

“I kept my mind on it,” replied the sailor, “but when one has been tossed about like we were, so small an object can easily disappear. Even my pipe is gone. Where can the damn box be?”

“Well, the tide is going down,” said Herbert, “let us go round to the spot where we landed.”

There was little chance that they would recover this box that the waves had tossed among the rocks at high tide but it was worth a try under the circumstances. Herbert and Pencroff ran to the spot where they had landed earlier about two hundred feet from the Chimneys.

There, among the pebbles, in the cavities of the rocks, they searched carefully. The result: nothing. If the box had fallen in this vicinity it must have been swept away by the waves. As the sea went down the sailor searched every crevice in the rocks without finding anything. It was a serious loss under the circumstances and for the moment irreparable.

Pencroff found it hard to hide his disappointment. His brow wrinkled up. He didn’t say a word. Herbert wanted to console him by observing that, very likely, the matches would have been wet from the sea water and would have been useless.

“But no, my boy,” replied the sailor. “They were in a tightly closed copper box! And now what are we to do?”

“We will certainly find some means of making fire,” said Herbert. “Mr. Smith or Mr. Spilett would not be at a loss like we are.”

“Yes,” replied Pencroff, “but meanwhile we are without fire and our companions will find a sorry meal on their return.”

“But,” said Herbert briskly, “isn’t it possible that they have tinder or matches?”

“I doubt it,” replied the sailor shaking his head. “First of all Neb and Mr. Smith do not smoke, and I really believe that Mr. Spilett would rather save his notebook than his box of matches.”

Herbert did not reply. The loss of the box was obviously a regrettable thing. However, the lad counted on making a fire by one means or another. Pencroff, who was more experienced, did not think so, though he was not a man to be bothered by a small or a large inconvenience. In any event, there was only one course to take: wait for the return of Neb and of the reporter. But it was necessary to forget about the meal of hard eggs that they had wanted to prepare for them and a diet of raw meat either for themselves or for the others did not appear to be an agreeable prospect.

Before returning to the Chimneys the sailor and Herbert collected a new batch of lithodomes in the event that there definitely would be no fire. They went back silently on the path to their dwelling.

Pencroff, his eyes fixed on the ground, was still looking for the lost box. He even ascended again the left bank of the river from the mouth to the bend where the raft of wood had been moored. He returned to the upper plateau. He went over it in every direction, he searched among the tall grass along the border of the forest—all in vain.

It was five o’clock in the evening when Herbert and he returned to the Chimneys. Needless to say they rummaged through the darkest corners of the passageways but they definitely had to give up. About six o’clock, at the time when the sun was disappearing behind the highlands of the west, Herbert, who was pacing back and forth on the shore, signaled the return of Neb and of Gideon Spilett.

They were returning alone!... His heart skipped a beat. The sailor had not been deceived by his misgivings. The engineer Cyrus Smith had not been found!

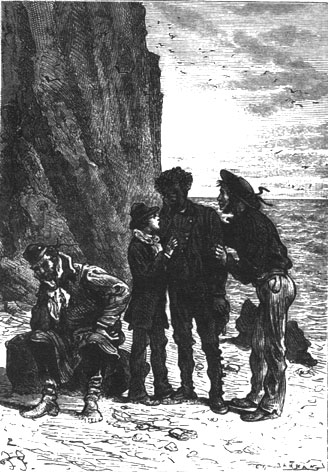

On arriving the reporter sat down on a rock without saying a word. Exhausted and dying of hunger he did not have the strength to say a word.

The reporter sat down on a rock without saying a word.

As to Neb his red eyes showed that he had cried and the new tears that he could not hold back showed only too clearly that he had lost all hope!

The reporter told them about the search that they had undertaken to find Cyrus Smith. Neb and he had followed the coastline for a distance of more than eight miles and consequently well beyond the point where the next to the last fall of the balloon occurred, the fall that was followed by the disappearance of the engineer and the dog Top. The shore was deserted. Not a trace, not a single footprint. Not a stone recently overturned, not a sign on the sand, no mark of the human foot on all of this part of the coast. It was evident that no inhabitant ever frequented this portion of the shore. The ocean was just as deserted as the beach and it was there, several hundred feet from shore, that the engineer had met his fate.

Then Neb got up and voiced the sentiments of hope that were bottled up within him:

“No!” he shouted. “No! He is not dead! No! That cannot be! He! Come now! It might happen to me or anyone else but him! Never! He could get out of any scrape!...”

Then his strength left him.

“Ah!, I can do no more,” he murmured.

Herbert ran to him.

“Neb,” said the lad, “we will find him! God will return him! But now you are hungry. Eat, eat a little, I beg you.”

And, while speaking, he offered the poor negro a handful of shellfish, a meager and insufficient nourishment.

Neb had not eaten for many hours but he refused. Deprived of his master he could not, he did not want to live!

As to Gideon Spilett, he devoured these mollusks. Then he lay down on the sand in front of a rock. He was worn out but calm. Herbert came up to him and offered him his hand:

“Sir,” he said, “we have discovered a shelter where you will be better off than here. It is getting dark. Get some rest. Tomorrow we will see...”

The reporter got up and, guided by the lad, he went toward the Chimneys.

Pencroff came over to him and asked him in a casual voice if by chance he had a match on him.

The reporter stopped, looked in his pockets, and didn’t find any. He said, “I had some but I must have thrown them away...”

The sailor then spoke to Neb. He asked the same question and got the same reply.

“Damn it!” cried the sailor, who could not hold back this word. The reporter heard him and going to Pencroff he said, “You have no matches?”

“Not a single one, and consequently we have no fire!”

“Ah!” shouted Neb, “If my master were here he would know how to make it!”

The four castaways stood there and looked at each other not without some uneasiness. It was Herbert who first broke the silence by saying:

“Mister Spilett, you are a smoker. You always have matches on you. Perhaps you have not looked thoroughly. Look again. A single match will suffice.”

The reporter rummaged again through his pants pockets, his waistcoat, his overcoat and finally to Pencroff’s great joy as well as to his own surprise he felt a piece of wood caught in the lining of his waistcoat. His fingers seized this small piece of wood through the fabric but he could not get it out. Since this was only one match they must not rub the phosphorous.

“Will you let me try it?” the lad asked him.

Very skillfully, without breaking it, he succeeded in removing this small piece of wood, this wretched and precious flare which for these poor people was of such importance. It was intact.

“A match!” shouted Pencroff. “Ah! It’s as if we had a whole cargo!”

He took the match and followed by his companions he went back to the Chimneys.

This small piece of wood which in civilized countries is lavished with indifference and has no value would have to be used here with extreme care. The sailor assured himself that it was really dry. That done he said, “We need some paper.”

“Here,” replied Gideon Spilett, who tore out a leaf from his notebook after some hesitation.

Pencroff took the piece of paper that the reporter gave him and he squatted in front of the fireplace. There several handfuls of grass, leaves and dry moss were placed under the faggots and arranged so that the air could easily circulate and the dead wood would catch fire quickly.

Then Pencroff folded the paper in the form of a cone, as smokers do in a high wind, and placed it among the mosses. Next taking a rather flat stone he wiped it with care. With his heart beating fast he gently rubbed the stone without breathing.

The first rubbing produced no effect. Pencroff had not applied enough pressure fearing that he would scratch the phosphorous.

“No, I can’t do it,” he said, “my hand trembles... The match did not catch fire... I cannot... I don’t want to,” and getting up he asked Herbert to take his place.

Certainly in all his life the lad had not been so nervous. His heart beat fast. Prometheus going to steal fire from Heaven had not been more anxious. He did not hesitate however and quickly rubbed the stone. They heard a sputter then a weak blue flame spurted out producing a sharp flame. Herbert gently turned the match so as to feed the flame, then he slipped it into the paper cone. The paper caught fire in a few seconds and the moss also caught.

Several moments later the dry wood crackled and a joyful flame, activated by the sailor’s vigorous breath, developed in the midst of the obscurity.

“Finally,” shouted Pencroff, getting up. “I was never so nervous in my life!”

“I was never so nervous in my life!”

The fire certainly burned well on the fireplace of flat stones. The smoke went easily through the narrow passage, the chimney drew the smoke and a pleasant warmth spread out.

As to the fire, they had to take care not to let it burn out and to always keep some embers under the ashes. But this was merely a matter of care and attention since there was no shortage of wood and their supply could always be renewed at their convenience. Pencroff first intended to use the fireplace to prepare a supper more nourishing than a dish of lithodomes. Herbert brought over two dozen eggs. The reporter, resting in a corner, watched these preparations without saying a word. Three thoughts were on his mind. Was Cyrus still alive? If he was alive where could he be? If he had survived his fall why had he not made his existence known? As to Neb, he prowled the beach. He was a body without a soul.

Pencroff, who knew fifty two ways to make eggs, had no options at the moment. He had to be content to introduce them among the warm cinders and to let them harden at a low heat.

In several minutes the baking took effect and the sailor invited the reporter to take his share of the supper. Such was the first meal of the castaways on this unknown shore. These hard eggs were excellent and since the egg contains all the elements needed for man’s nourishment these poor people found themselves well off and felt strengthened.

Ah! If only one of them had not been missing at this meal! If the five prisoners who escaped from Richmond could all have been there under this pile of rocks in front of this bright crackling fire on this dry sand, what thanks they would have given to Heaven! But the most ingenious, also the wisest, he who was their unquestioned chief, Cyrus Smith, was missing alas and his body had not even had a decent burial!

Thus passed the day of March 25. Night came. Outside they heard the wind whistling and the monotonous surf beating against the shore. The pebbles, tossed around by the waves, rolled about with a deafening noise.

The reporter retired on the floor of one of the corridors after having quickly noted the incidents of the day: the first appearance of this new land, the disappearance of the engineer, the exploration of the coast, the incident with the matches, etc.; and aided by fatigue he succeeded in finding some sleep.

Herbert slept well. As to the sailor, he spent the night with one eye on the fire and spared no fuel.

Only one of the castaways did not rest in the Chimneys. It was Neb, forlorn and without hope, who for the entire night, in spite of the pleadings of his companions to take some rest, wandered on the shore calling for his master!