The bank was elevated.

It was six o’clock in the morning when the colonists, after an early meal, took to the road with the intention of reaching the western coast of the island by the shortest way. How much time would be needed to get there? Cyrus Smith had said two hours but that evidently depended on the nature of the obstacles that would present themselves. This part of the Far West seemed crowded like an immense cospe composed of extremely varied species. It was therefore likely that they would have to blaze a trail through the grass, the brushwood, and the creepers and march with axe in hand—and gun also doubtless, judging from the cries of the animals heard in the night.

The exact position of the encampment was determined by the location of Mount Franklin and since the volcano rose in the north at a distance of less than three miles, they must take a straight route to the southwest to reach the western shore.

They left after having carefully moored the canoe. Pencroff and Neb carried the provisions which would suffice to feed the small troop for a least two days. There was no thought of hunting and the engineer even recommended to his companions that they avoid any impulsive gunshots in order not to signal their presence to anyone on shore.

The first blows of the axe were made against the brushwood, among the mastic tree bushes a little above the cascade. With compass in hand, Cyrus Smith indicated the direction to follow.

The forest was composed, for the most part, of trees already recognized in the neighborhood of the lake and Grand View Plateau. They were deodars, douglas, casuarinas, gum trees, eucalyptus, dragon trees, hibiscus, cedars and other species, generally of a mediocre height because their number hindered their development. The colonists could only advance slowly on this path that they had blazed in a region which, in the engineer’s opinion, had to be linked further on to Red Creek.

After their departure, the colonists descended the lower slopes that made up the mountain system of the island, on a very dry terrain but whose luxurious vegetation left the feeling of the presence of an underground network of some nearby stream. However, Cyrus Smith did not remember having recognized, at the time of his excursion to the crater, any other watercourses than those of Red Creek and the Mercy.

During the first hours of the excursion they again saw monkeys who seemed to show astonishment at the sight of men whose aspect was new to them. Gideon Spilett asked humorously if the agile and robust quadrumanes did not consider his companions and him as degenerate brothers! And frankly, these simple pedestrians, obstructed at each step by underbrush, entangled by creepers, barred by tree trunks, did not distinguish themselves compared to these supple animals who bounded from branch to branch and were stopped by nothing in their path. There were numerous monkeys but very fortunately they did not manifest any hostile disposition.

They also saw several wild boar, agoutis, kangaroos and other rodents and two or three koalas whom Pencroff would have willingly greeted with gunshots.

“But,” he said, “hunting is not allowed. Skip about then, my friends, jump and fly in peace! We will have a few words to say to you on our return!”

At nine thirty in the morning the road, which headed directly to the southwest, suddenly found itself barred by an unknown watercourse thirty to forty feet wide, whose vivid current, propelled by its slope and broken by numerous rocks, fell with a grating noise. The creek was deep and clear but it was absolutely unnavigable.

“We are cut off!” cried Neb

“No,” replied Herbert, “it is only a stream and we will be able to swim across.”

“What for?” replied Cyrus Smith. “It is evident that this creek runs to the sea. Let us remain on its left, following the bank and I will not be surprised if we promptly reach the coast. Let’s go.”

“One moment,” said the reporter. “The name of this creek, my friends? Let us not leave our geography incomplete.”

“Right,” said Pencroff.

“Name it, my child,” said the engineer, addressing the lad.

“Would it not be better to wait until we reach the mouth?” noted Herbert.

“So be it,” replied Cyrus Smith. “Let us follow it then without stopping.”

“Wait another moment,” said Pencroff.

“What is it?” asked the reporter.

“If hunting is prohibited, fishing is permitted, I suppose,” said the sailor.

“We have no time to lose,” replied the engineer.

“Oh!, five minutes!” replied Pencroff. “I only ask five minutes in the interest of our lunch.”

And Pencroff, lying down on the bank, plunged his arms into the vivid water and soon made several dozen beautiful crayfish skip about as they swarmed among the rocks.

“This will be good!” cried Neb, coming to help the sailor.

“I tell you that, except for tobacco, there is everything on the island!” murmured Pencroff with a sigh.

It did not take five minutes for this wonderful fishing because the crayfish swarmed about the creek. These shellfish, whose shell has a cobalt blue color, have a snout armed with a small tooth. They filled up a sack and went on their way.

Since following the bank of the new watercourse, the colonists marched more easily and rapidly. Moreover, the banks were free of any human traces. From time to time they picked up some traces left by large animals who came regularly to quench their thirst at this stream, but notwithstanding, it still was not in this part of the Far West that the peccary had received the lead bullet which had cost Pencroff a molar.

However, on considering how rapidly the current flowed toward the sea, Cyrus Smith was lead to suppose that his companions and he were further from the western coast than he believed. And in fact, at this hour the tide was rising on shore and it should have turned back the creek’s current if its mouth was only several miles away. Now this effect was not produced and the flow followed its natural slope. The engineer was very astonished at this and he frequently consulted his compass in order to assure himself that some detour in the river was not leading them into the interior of the Far West.

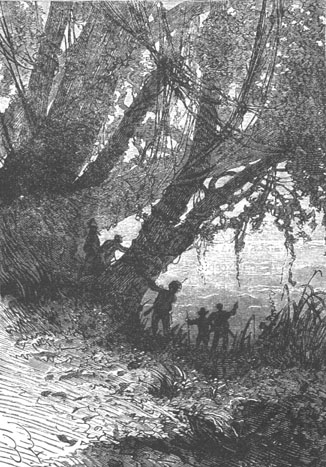

However, the creek became wider and little by little its waters became less tumultuous. The trees on the right bank were as crowded as those on the left bank and it was impossible to see beyond. These woods were certainly deserted because Top did not bark and the intelligent animal would not have neglected to signal the presence of any strangers in the neighborhood of the watercourse.

At ten thirty, to the great surprise of Cyrus Smith, Herbert, who was a little ahead, suddenly stopped and cried:

“The sea!”

And several moments later, stopping at the edge of the forest, the colonists saw the western shore of the island develop before their eyes.

But what a contrast between this coast and the eastern coast on which chance had first thrown them! No granite wall, no reef, not even a sandy beach. The forest formed the shore and its last trees, battered by the waves, leaned over the water. It was not a shore such as nature usually makes, covered with either sand or rocks, but an admirable border made up of the most beautiful trees in the world. The bank was elevated so that it was higher than level of the highest tides, and the luxuriant soil was supported by a granite base. The splendid forest species seemed to be as firmly planted as any in the interior of the island.

The bank was elevated.

The colonists found themselves at the opening of a small unimportant cove which could not even hold two or three fishing boats, and which served as the narrow entrance to the new creek; but this was the curious thing, that the water, instead of reaching the sea by a gentle slope, fell from a height of more than forty feet—this explained why, at the time of high tide, it was not felt upstream. In fact, the tides of the Pacific, even at their maximum elevation, could never reach the level of the river whose bed was elevated, and doubtless millions of years would pass before the waters would erode this wall of granite and form a practical opening. They agreed to give this watercourse the name of “Falls River.”

Beyond, toward the north, the shore, formed by the forest, extended for a distance of about two miles; then the trees became scarce and beyond that were very picturesque heights following a nearly straight line which ran from north to south. In contrast, over the entire portion of the shore between Falls River and Reptile Promontory, there were only woods with magnificent trees, some straight, others bending over with the long waves of the sea bathing their roots. Now it was on this coast, that is to say over the entire Serpentine Peninsula, that the exploration had to be continued because this part of the shore offered a refuge that the other, arid and savage, did not provide for any castaways whoever they were.

The weather was beautiful and clear, and at the top of a cliff on which Neb and Pencroff set out lunch, the view extended quite far. The horizon was perfectly distinct and there were no sails there. Over all of this shore, as far as the view could extend, there was no vessel, not even a wreck. But the engineer would establish this only when he had explored the coast up to the very extremity of Serpentine Peninsula.

They quickly finished lunch and at eleven thirty Cyrus Smith gave the signal to leave. Instead of traveling at the edge of a cliff or on a sandy shore, the colonists would have to follow the line of trees running along the coast.

The distance which separated the mouth of Falls River from Reptile Promontory was about twelve miles. In four hours on a practical shore, without rushing, the colonists would have been able to cross this distance; but it would require twice this time to reach their goal, what with trees to go around, brushwood to cut, creepers to break and the detours which would lengthen the distance.

Moreover, there was nothing to indicate a recent wreck on this shore. It was true, as Gideon Spilett noted, that the sea was able to wash away anything, and that they should not conclude that, because they found no traces, that a vessel had not been thrown on the coast on this part of Lincoln Island.

The reporter’s reasoning was justified and besides, the incident of the lead bullet proved positively that in the last three months at most, a gun had been fired on the island.

It was already five o’clock and the extremity of Serpentine Peninsula was still two miles away. It was evident that after having reached Reptile Promontory, Cyrus Smith and his companions would no longer have the time to return before sundown to the encampment that they had established near the sources of the Mercy. It would then be necessary to pass the night at the promontory itself. But provisions were not lacking which was fortunate because furry game no longer showed itself on this shore. To the contrary, birds abounded here, jacamars, couroucous, trogons, grouse, lorries, parakeets, cockatoos, pheasants, pigeons and a hundred others. There was not a tree without a nest and not a nest that was not full of flapping wings.

Around seven o’clock in the evening, the colonists, weary with fatigue, arrived at Reptile Promontory, a sort of volute strangely cut out of the sea. Here ended the forest of the peninsula. The entire southern part of the coast again took on the usual look of a shore with its rocks, its reefs and its beaches. It was therefore possible that a disabled vessel could take refuge on this portion of the island, but with night coming on it would be necessary to put off the exploration to the next day.

Pencroff and Herbert immediately began to look for a good place to establish a camp. The last trees of the forest of the Far West died out at this point and among them the lad recognized some thick bamboo clusters.

“Good!” he said. “Here is a precious discovery.”

“Precious?” replied Pencroff.

“Without doubt,” answered Herbert. “I can tell you, Pencroff, that bamboo bark, cut into flexible lath, serves to make baskets; that this bark, reduced to a paste and macerated, serves to make rice paper; that the stems are used, according to their size, for canes, tobacco pipes and water pipes; that large bamboos form an excellent construction material, light and sturdy, which are never attacked by insects. I should even add that by sawing the bamboo internodes and keeping for the bottom a portion of the transverse partition which forms the node, sturdy and handy pots are obtained which are very much in use in China! No! That does not satisfy you. But...”

“But?...”

“But I will tell you, if you don’t know it, that in India they eat these bamboos like asparagus.”

“Asparagus thirty feet high!” cried the sailor. “And are they good?”

“Excellent,” replied Herbert. “Only it is not the thirty foot high stalks that they eat but the young bamboo shoots.”

“Perfect, my boy, perfect!” replied Pencroff.

“I will also add that the pith of the new stalks, pickled in vinegar, makes a very appreciated condiment.”

“Better and better, Herbert.”

“And finally, that these bamboos exude a sweet liqueur between their nodes from which a very agreeable beverage can be made.”

“Is that all?” asked the sailor.

“That is all!”

“And anything to smoke, perchance?”

“Nothing to smoke, my poor Pencroff!”

Herbert and the sailor did not look long for a favorable place to pass the night. The high rocks on the shore—very broken up because they were violently battered by the sea under the influence of the winds from the southwest—presented hollows which would permit them to sleep sheltered from the weather. But at the moment when they were about to enter one of these excavations, some formidable roaring stopped them.

“Get back!” cried Pencroff. “We only have some small pellets in our guns, and beasts that roar so well would be as troubled with them as with a grain of salt!”

And the sailor, seizing Herbert by the arms, dragged him to the shelter of the rocks just as a magnificent animal showed itself at the entrance to the cavern.

It was a jaguar of a size at least equal to that of its congeners of Asia, that is to say that it measured more than five feet from the extremity of its head to the beginning of its tail. Its fawn colored fur was enhanced by several rows of regularly marked black spots and with white fur on its belly. Herbert recognized this ferocious rival of the tiger, as terrible as the cougar.

The jaguar advanced and looked around himself, fur bristling, eyes on fire, as if he had not sensed man for the first time.

At this moment the reporter came around the high rocks and Herbert, thinking that he had not seen the jaguar, went toward him; but Gideon Spilett motioned to him and continued walking. This was not his first tiger and he advanced to within ten feet of the animal and remained immobile, the carbine to his shoulder without a muscle trembling.

The jaguar gathered himself together and pounced on the hunter but at that moment a ball struck him between the eyes and he fell dead.

A ball struck him between the eyes.

Herbert and Pencroff ran toward the jaguar. Neb and Cyrus Smith rushed up from their side and they took a few moments to look at the animal stretched out on the ground. Its magnificent fur would make an ornament in the large hall of Granite House.

“Ah, Mister Spilett. How I admire you and envy you,” cried Herbert, in a fit of rather natural enthusiasm.

“Well, my boy,” replied the reporter, “you would have done as well.”

“Me! Such coolness...”

“Imagine, Herbert, that the jaguar is a hare, and you will shoot more calmly than anyone.”

“There!” replied Pencroff. “It is not more difficult than that!”

“And now,” said Gideon Spilett, “since the jaguar has left his den, my friends, I do not see why we should not occupy it for the night.”

“But others may return!” said Pencroff.

“It will suffice to light a fire at the entrance to the cavern,” said the reporter, “and they will not venture to cross the threshold.”

“To the jaguar’s house then!” replied the sailor, dragging the animal’s body behind him.

The colonists went toward the abandoned den and there, while Neb skinned the jaguar, his companions piled up on the threshold a large quantity of dry wood which the forest furnished abundantly.

But Cyrus Smith, seeing the bamboo clusters, went to cut a certain quantity which he mixed with the fuel for the fire.

That done, they installed themselves in the grotto whose sand was strewn with bones; the guns were armed for any emergency in case of a sudden attack; they supped and then, when it came time to go to sleep, they set fire to the wood piled up at the entrance to the cavern.

A crackling noise soon burst out. It was the bamboo, reached by the flames, which detonated like firecrackers. Nothing but this noise would suffice to frighten the most audacious animals.

And this means of producing vivid detonations was not the engineer’s invention. According to Marco Polo, the Tartars, over the centuries, used it with success to drive the dreaded beasts of central Asia away from their encampments.