The colonists dressed again in white linen.

The first week in January was devoted to making the linen needed by the colony. The needles found in the case were used by vigorous if not sturdy fingers and the sewing was done well.

There was no lack of thread thanks to Cyrus Smith’s idea of using the thread that had already served to sew up the balloon. These long threads were unraveled by Gideon Spilett and Herbert with admirable patience. Pencroff had to give up this work which irritated him beyond measure; but when it came to sewing, he had no equal. No one can be ignorant of the fact that sailors have a remarkable aptitude for the sewing profession.

The cloth that composed the envelope of the balloon was then degreased by means of soda and potassium obtained from the incineration of plants so that the unvarnished cotton regained its suppleness and its natural elasticity; then subjected to the decoloration action of the atmosphere, it acquired a perfect whiteness.

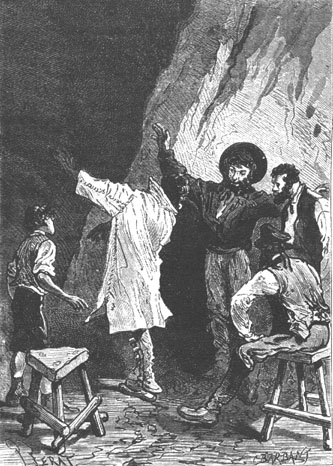

Several dozen shirts and socks—the latter unknitted of course but made of sewn cloth—were made. What pleasure it was for the colonists to dress again in white linen—very rough linen doubtless but they were not troubled by so small a matter—and to sleep between sheets which made the bunks of Granite House into quite substantial beds.

The colonists dressed again in white linen.

It was also about this time that they made sealskin shoes, which opportunely replaced the shoes and the boots brought from America. These new shoes were large and wide and never pinched their feet.

The heat was still with them at the beginning of the year of 1866 but that did not stop the hunting in the woods. Agoutis, peccaries, capybaras, kangaroos, hairy and feathery game truly abounded and Gideon Spilett and Herbert were good archers who did not waste a shot.

Cyrus Smith recommended that they economize on munitions and he took measures to replenish the powder and the lead shot that had been found in the case and which he wished to save for the future. Who could know what hazards they would face one day in the event that they left their domain? They must prepare for future uncertainties by economizing their munitions and substitute for them other easily renewable substances.

As to replacing the lead of which Cyrus Smith had found no trace on the island, he used, without detriment, small iron shot which was easy to make. These grains were not as heavy as the lead grains so they made them larger. Each charge contained less but the skill of the hunters made up for the deficiency. As to the powder, Cyrus Smith would have been able to make it since he had available saltpeter, sulphur and coal but this preparation required extreme care and without special tools it was difficult to produce in good quality.

Cyrus Smith preferred to make pyroxyle, that is to say guncotton, a substance in which cotton in not necessary except for the cellulose. Now cellulose is nothing more than the elementary tissue of plants and it is found in a nearly perfect state of purity not only in cotton but in the fibrous textiles of hemp and flax, in paper, old linen, elder pith, etc. Now elder trees abounded on the island near the mouth of Red Creek. The colonists had already used the berries of these shrubbery trees of the honeysuckle family as a coffee.

It was sufficient to collect the elder pith, that is to say the cellulose. The only other substance necessary for making pyroxyle was fuming nitric acid. Now, since Cyrus Smith had sulphuric acid available, he had already produced nitric acid easily by attacking saltpeter which was furnished by nature.

He therefore resolved to make and use pyroxyle although he was aware of its rather serious disadvantages, that is to say a large variation in effect, an excessive inflammability since it ignites at 170° instead of 240° and finally a too rapid detonation which could damage the guns. On the other hand, the advantages of pyroxyle are these, that it is not altered by humidity, that it does not foul up the gun and that its explosive force is quadruple that of ordinary powder.

To make pyroxyle, it suffices to submerge the cellulose into fuming nitric acid for a quarter of an hour, then to wash it with water and dry it over a large fire. One can see that nothing is simpler.

Cyrus Smith only had the ordinary nitric acid and not the fuming nitric acid or the monohydrate, that is to say the acid which emits white vapors on contact with humid air; but the engineer could substitute for the latter and obtain the same result by mixing ordinary nitric acid with sulphuric acid in the ratio of three to five by volume. This he did. The hunters soon had a well made substance which gave excellent results when used with discretion.

About this time the colonists cleared three acres1 of Grand View Plateau and the remainder was saved in the prairie state for the use of the onagers. Several excursions were made into the Jacamar and Far West forests and they brought back a true harvest of wild vegetables, spinach, cress, horse radish and turnips which would soon be cultivated. This would improve their diet. They also carried a lot of wood and coal. Each excursion had, at the same time, improved the roadway which settled down little by little under the wheels of the cart.

The warren continued to furnish its quota of rabbits for the Granite House pantry. Since it was located just beyond Glycerin Creek, its hosts could not penetrate the guarded plateau nor ravage the newly made plantation. As to the oyster bed, located among the rocks of the beach and whose products were frequently renewed, it yielded excellent mollusks daily. Fishing either in the waters of the lake or in the Mercy was worthwhile because Pencroff had made some lines armed with iron hooks which frequently caught fine trout and certain extremely savoury fish whose silvery sides were covered with small yellow spots. In this way Master Neb, in charge of the culinary department, was able to agreeably vary the menu at each meal. Bread alone was still missing from the colonists’ table and, as was said, it was a privation which was truly felt.

About this time they also hunted the tortoises which frequented the beaches of Cape Mandible. In this region the shore bristled with small mounds covering perfectly spherical eggs with a hard white shell whose albumin does not coagulate like bird eggs. It was the sun that made them hatch. There naturally was a considerable number since each tortoise can lay up to two hundred fifty annually.

“A real egg field,” said Gideon Spilett, “and we have only to collect them.”

But they were not content with these products. They also had a hunt for the producers, a hunt which allowed them to carry back to Granite House a dozen of these chelonians, truly very valuable from the alimentary point of view. Tortoise soup, enhanced with aromatic herbs and cruciferae, often drew merited praise for its preparer, Master Neb.

A happy circumstance should be cited here, which allowed them to make additional provisions for the winter. Schools of salmon ventured into the Mercy and ascended the watercourse for several miles. This was the season in which the females, seeking suitable places for spawning, precede the males and make a lot of noise swimming through the sweet water. A thousand of these fish, which measured up to two and a half feet in length, crowded the river and they caught a large quantity by establishing several dams. Several hundred were salted and put in reserve for the time when winter, freezing the watercourse, would render all fishing impractical.

It was at this time that the very intelligent Jup was promoted to the rank of valet. He had been dressed in a jacket, short breeches of white cloth, and an apron with pockets that he liked to shove his hands into. He did not mind that they saw him fumbling. The skillful orang had been well trained by Neb and one would say that the Negro and the ape understood each other when they chatted. Jup had, besides, an actual sympathy for Neb and Neb reciprocated. Unless they had need for his services, be it to haul some wood or to climb to the top of some tree, Jup passed most of his time in the kitchen trying to imitate Neb in everything that he saw him do. Besides, the master showed patience and even an extreme zeal in instructing his pupil and the pupil showed a remarkable intelligence in profiting from the lessons given to him by his master.

Jup passed most of his time in the kitchen.

One can judge the satisfaction that he gave to the hosts of Granite House when one day, without any previous announcement, he came with a table napkin on his arm, ready to serve at the table. Skillful and attentive, he performed perfectly, changing the napkins, carrying the plates, pouring the drinks, all with a seriousness that amused the colonists to the last degree and delighted Pencroff.

“Jup, some soup!”

“Jup, a little agouti!”

“Jup, a napkin!”

“Jup! Worthy Jup! Honest Jup!”

Without becoming upset, Jup responded to everyone and observed everything. He shook his intelligent head when Pencroff, alluding to his joke on the first day, said to him:

“Decidedly Jup, we must double your wages!”

Needless to say, the orang had become completely acclimatized to Granite House and he often accompanied his masters into the forest without ever manifesting any desire to escape. At such times he marched in the most amusing fashion, with a cane that Pencroff had given him, carrying it on his shoulder like a gun. If they had to pluck some fruit from the top of a tree, how quickly he was up there! If the wheel of the cart became stuck in the mud how vigorously Jup got it back on the road with a single shove!

“What a rascal!” Pencroff often cried. “If he was as mischievous as he is good, there would be no holding him back.”

It was toward the end of January that the colonists undertook a large task in the central part of the island. It had been decided that at the foot of Mount Franklin near the sources of Red Creek, they would build a corral designed to hold the ruminants whose presence near Granite House would have been a nuisance, and especially those wild sheep which could furnish the wool that they expected to make into winter clothing.

Every morning the colony, sometimes in its entirety, more often represented only by Cyrus Smith, Herbert and Pencroff, went to the sources of the creek with the aid of the onagers. This was a promenade of not more than five miles under a dome of verdure on this newly traced route which took the name of “Route to the Corral.”

There a large piece of ground had been chosen on the very flank of the southern part of the mountain. It was a prairie, planted with clusters of trees, situated at the very foot of a buttress which enclosed it on one side. A small brook, having its source among the slopes, flowed diagonally across the area and fed into Red Creek. The grass grew well and the few trees allowed the air to circulate freely. It sufficed then to enclose the said prairie with a palisade which would be supported at each corner by a buttress. Being rather high, the most agile animals would not be able to cross it. This enclosure would contain, at any one time, about a hundred horned animals, wild sheep or goats, with young that would be born in time.

The perimeter of the corral was marked off by the engineer and they then proceeded to cut the trees needed to construct the palisade; but, since in making the road it had already been necessary to sacrifice about a hundred trees, they were used as stakes which were firmly planted in the ground.

At the front of the palisade, a rather large entrance was arranged and closed with two swing doors made of very thick planks which could be shut by exterior cross bars.

The construction of the corral required not less than three weeks because in addition to the work on the palisade, Cyrus Smith built large planked sheds under which the ruminants could find shelter. Besides, it had been necessary to make it very sturdy because wild sheep are robust animals and their first violence was to be feared. The stakes, pointed on top and hardened in fire, were made strong by means of regularly placed iron bolts which assured the strength of the entire structure.

The corral finished, a game drive was then undertaken to the foot of Mount Franklin amid the pastures frequented by the ruminants. This operation was made on the 7th of February, a fine summer day and everyone took part in it. The two onagers, well broken in by this time, were mounted by Gideon Spilett and Herbert and rendered a useful service on this occasion.

The maneuver consisted simply of pressing down on the sheep and goats and little by little narrowing the field of battle around them. Cyrus Smith, Pencroff, Neb and Jup posted themselves at various points in the woods, while the two horsemen and Top galloped within a radius of a half a mile around the corral.

The wild sheep were numerous in this portion of the island. These fine animals, large as deer, horns stronger than those of a ram, with gray fleece blending with long hair, resembled argalis.

This hunting day was tiring. What comings and goings, crossing and criss-crossing and commotion! Of the hundred wild sheep surrounded, more than two thirds escaped; but in the end thirty of these ruminants and a dozen wild goats, driven little by little toward the corral whose open door seemed to offer an outlet, threw themselves inside and were imprisoned.

In sum the result was satisfying and the colonists could not complain. For the most part, these wild sheep were females, several of whom would not be long in giving birth. It was certain that the flock would prosper not only to provide wool but also hides in the not too distant future.

That evening the hunters returned to Granite House exhausted. However, the next day they returned, at least to visit the corral. The prisoners had been trying to turn over the palisade but they had not succeeded and they were not long in becoming more tranquil.

During the month of February no important event occurred. The daily tasks were regularly pursued. At the same time as they improved the roads to the corral and to Port Balloon, a third was begun from the enclosure to the western shore. The deep woods which covered Serpentine Peninsula were still an unknown portion of Lincoln Island. Gideon Spilett counted on purging from his domain the wild beasts that took refuge there.

Before the return of the cold season, the most assiduous care was given to the cultivation of the wild plants that had been transplanted from the forest to Grand View Plateau. Herbert hardly ever returned from an excursion without bringing back some useful vegetable. One day it was a specimen of the chicoriaceae species whose seed, under pressure, makes an excellent oil; on another day it was the common sorrel whose antiscorbutic properties are not to be disdained; then some of the precious tubercles which have been cultivated at all times in South America, these potatoes which nowadays are counted as more than two hundred species. The kitchen garden, now in good repair, well watered and well defended against birds, was divided into small plots where lettuce, kidney beans, sorrel, turnips, horse radish and other cruciferous plants grew. The earth of the plateau was very fertile and they could hope that the harvest would be abundant.

Various beverages were no longer lacking and, on the condition that one did not ask for wine, the most difficult people would have no cause to complain. To the Oswego tea furnished by the didymous monarda and the fermented liqueur extracted from the dragon tree roots, Cyrus Smith had added a real beer; he made it with the young shoots of the “abies nigra” which, after having been boiled and fermented, gave a particularly healthy and pleasant beverage which the Anglo-Americans call “spring beer,” that is to say fir tree beer.

About the end of the summer the poultry yard possessed a fine pair of bustards who belonged to the “houbara” species characterized by a sort of apron of feathers, a dozen shovellers, whose upper jaw is extended on each side by a membranous appendage, and some magnificent black crested cocks with a carbuncle and epidermis resembling the cocks of Mozambique, who strutted on the banks of the lake.

Thus everything was successful thanks to the activity of these courageous and intelligent men. Providence had doubtless done much for them; but faithful to principles, they had first helped themselves and heaven came to their aid afterwards.

At the end of a warm summer’s day, when work was finished and a breeze came up from the sea, they loved to sit at the edge of Grand View Plateau under a sort of veranda covered with creeping vines that Neb had erected with his own hands. There they chatted, they instructed one another, they made plans, the sailor’s good humor always entertaining this small world in which perfect harmony never ceased to reign.

They also spoke of their country, of dear and wonderful America. What of the War of Secession? It evidently could not have continued. Richmond had doubtless fallen promptly into the hands of General Grant! The capture of the Confederate capital had to be the last act of this deadly struggle! Now the North had triumphed for a good cause. Ah! How a newspaper would have been welcomed by the exiles of Lincoln Island! For eleven months all communication between them and the rest of humanity had been interrupted and in a little while the 24th of March would mark the anniversary of the day when the balloon had thrown them on this unknown shore! Then they were only castaways, not even knowing if they could wrest a miserable existence from the elements. And now thanks to the knowledge of their chief, thanks to their own intelligence, they were true colonists, provided with arms, tools and instruments, who had known how to transform to their profit the animals, plants and minerals of the island, that is to day the three kingdoms of nature.

Yes! They often spoke of these things and made additional plans for the future!

As to Cyrus Smith, for the most part silent, he listened to his companions more often than he spoke. Now and then he smiled at some of Herbert’s thoughts or at some of Pencroff’s witticisms but, at all times and everywhere he thought about those inexplicable events, about this strange enigma whose secret still escaped him.