Top came to visit his friend.

That same evening the hunters returned, having had a good hunt and literally loaded down with game. They carried all that four men could carry. Top had a string of pintail around his neck and Jup a belt of snipe around his body.

“Here master,” cried Neb, “here is something to employ our time with! Preserves, pies, we will have tasty dishes. But someone must help me. I am counting on you Pencroff.”

“No Neb,” replied the sailor, “the job of rigging the boat calls me, and you must do without me.”

“And you, Mister Herbert?”

“Me, Neb, I must go to the corral tomorrow,” replied the lad.

“Then will it be you, Mr. Spilett, who will help me?”

“To oblige you, Neb,” replied the reporter, “but I warn you that if you reveal your recipes to me I will publish them.”

“As you see fit, Mister Spilett,” replied Neb, “as you see fit.”

And that was how Gideon Spilett became Neb’s assistant and was installed the next day in his culinary laboratory. But previously the engineer had acquainted him with the result of the exploration that he had made on the previous day. In this respect the reporter agreed with Cyrus Smith that although nothing was found a secret still remained to be discovered.

The frost lasted for still another week and the colonists did not leave Granite House except for the attention needed by the poultry yard. The dwelling was fragrant with those good odors emitted from the learned manipulations of Neb and the reporter; but not all of the products of the marsh hunt were transformed into preserves and since the game kept well in this intense frost, the wild ducks and others were eaten fresh and declared superior to all other waterfowl of the known world.

During this week, Pencroff, aided by Herbert who skillfully handled the sailmaker’s needle, worked with such ardor that the boat’s sails were completed. There was no lack of hemp cord, thanks to the rigging which had been recovered from the balloon. The cables and the cordage of the net made excellent rope which the sailor put to good use. The sails had their edges stitched with strong bolt-ropes, but there still remained enough to make halyards, shrouds, sheets, etc. As to the tackles, Cyrus Smith fabricated the necessary pulleys by means of a lathe that he had made with Pencroff’s counsel. And so it happened that the rigging was completely ready before the boat was finished. Pencroff even made a red, white, and blue flag whose colors had been furnished by tinctorial plants which were very abundant on the island. Except that instead of the thirty seven stars representing the thirty seven states of the union which shine from the flags of American yachts, the sailor had added a thirty eighth, the star of “Lincoln State,” because he considered his island already a part of the great republic.

“And” said he, “it is so in heart if still not in fact.”

While waiting, the flag was unfurled at the main window of Granite House and the colonists saluted it with three hurrahs.

However they were approaching the end of the cold season and it seemed that this second winter would pass without any serious incident when, during the night of the 11th of August, Grand View Plateau was threatened with complete devastation.

After a very full day the colonists were in a deep sleep when about four o’clock in the morning they were suddenly awakened by Top’s barks.

This time the dog was not barking near the orifice of the well but at the threshold of the door and he threw himself upon it as if he wanted to push it open. Jup, on his part, uttered sharp cries.

“Well, Top!” shouted Neb, who was the first to awaken.

But the dog continued to bark more furiously.

“What is it?” asked Cyrus Smith.

And everyone, hurriedly dressing, ran toward the room’s windows which they opened.

Below was a layer of snow which barely appeared white on this very obscure night. The colonists saw nothing but they heard strange barks which burst out from the darkness. It was evident that the shore had been invaded by a certain number of animals that they could not make out.

“What are they?” shouted Pencroff.

“Wolves, jaguars, or apes!” replied Neb.

“The devil! But they can get to the top of the plateau,” said the reporter.

“And our poultry yard,” shouted Herbert, “and our plantations...”

“How did they get through?” asked Pencroff.

“They had to cross the bridge on the shore,” replied the engineer, “that one of us had forgotten to close.”

“In fact,” said Spilett, “I remember having left it open...”

“A fine thing you did there, Mister Spilett,” shouted the sailor.

“What is done is done,” replied Cyrus Smith. “What shall we do now?”

Such were the questions and answers which were rapidly exchanged between Cyrus Smith and his companions. It was certain that the bridge had been crossed, that the beach had been invaded by some animals, and that they, whatever they were, could ascend the left bank of the Mercy to reach Grand View Plateau. They must therefore hurry to fight them if need be.

“But what kind of animals are they?” Pencroff asked a second time just as the barks became louder.

These barks made Herbert shudder and he remembered having already heard them during his first visit to the sources of Red Creek.

“They are colpeos, they are foxes,” he said.

“Forward,” shouted the sailor.

And everyone, armed with axes, carbines and revolvers, threw themselves into the car of the elevator and set foot on the beach.

These colpeos are dangerous animals when there are many of them and they are provoked by hunger. Nevertheless the colonists did not hesitate to throw themselves into the midst of the band and their first revolver shots, lighting up the darkness, threw back the leading assailants.

It was important above all else, that they prevent these plunderers from reaching Grand View Plateau because the plantations and the poultry yard were at their mercy and immense damage, perhaps irreparable, would inevitably result especially to the cornfield. But since the invasion of the plateau could only be accomplished by passing on the left bank of the Mercy, it was sufficient to oppose the colpeos with an insurmountable barrier on this narrow section of the beach between the river and the granite wall. That was everyone’s opinion and upon Cyrus Smith’s order they reached the designated place while the colpeos were dashing about in the dark.

Cyrus Smith, Gideon Spilett, Herbert, Pencroff and Neb positioned themselves so as to form an uncrossable line. Top, with open jaws, preceded the colonists and he was followed by Jup, armed with a knotty cudgel, which he swung like a club.

It was very dark. It was only by the light of everyone’s firings that they could see the assailants. There were at least a hundred of them and their eyes shone like hot coals.

“They must not pass,” shouted Pencroff.

“They shall not pass,” replied the engineer.

But if they did not pass, it was not because they did not try. Those to the rear pushed against those in front and it was an incessant battle with revolver shots and axes. Many of the colpeos’ cadavers were already scattered on the ground, but the band did not seem to diminish. Others renewed their ranks by crossing the bridge on the shore.

Soon the colonists were forced to fight hand to hand not without receiving some wounds, light ones fortunately. Herbert, with a gunshot, got rid of a colpeo on Neb’s back who was fighting like a tigercat. Top was fighting furiously, lunging at the throats of the foxes and strangling them. Jup, armed with his club, was banging with all his might, and it was in vain that they tried to make him stay to the rear. Endowed doubtless with a vision that permitted him to pierce the darkness, he was always in the thickest part of the battle, uttering from time to time a sharp cry which for him was a sign of extreme jubilation. At one point he advanced so far that, from the light of a revolver, they could see him surrounded by five or six colpeos. He held up with coolness.

However the battle ended to the colonist’s advantage, but after they had fought for two long hours! The first rays of dawn doubtless made the assailants decide to retreat. They scampered off toward the north passing over the bridge which Neb immediately raised.

When day lighted up the field of battle, the colonists could count fifty bodies scattered on the beach.

“And Jup!” shouted Pencroff. “Where is Jup?”

Jup had disappeared. His friend Neb called him and for the first time Jup did not respond to his friend’s call.

Everyone set out to look for Jup, trembling that they might find him among the dead. They cleared away the bodies which stained the snow with their blood, and Jup was found in the midst of a veritable pile of colpeos whose jaws had been smashed and whose backs had been broken, bearing testimony that they had had to deal with the terrible cudgel of the fearless animal. Poor Jup still had his hand on the stump of his broken club; but deprived of his weapon, he had been overwhelmed by their numbers and his chest received deep wounds.

“He is alive!” shouted Neb, who leaned over him.

“And we will save him,” replied the sailor, “we will nurse him as if he were one of us!”

It seemed that Jup understood because he inclined his head on Pencroff’s shoulder as if to thank him. The sailor himself was wounded but these wounds, as well as those of his companions, were insignificant. Thanks to their guns, they had almost always kept their assailants at a distance. It was not so with the orang whose condition was serious.

Jup, carried by Neb and Pencroff, was brought to the elevator and it was with difficulty that a feeble groan left his lips. They lifted him gently to Granite House. There he was placed on a borrowed mattress on one of the bunks and his wounds were washed with the greatest care. It appeared that the wounds had not reached any vital organ but Jup was weak from the loss of blood and his fever was rather high.

They put him to bed after dressing his wounds and a severe diet was imposed on him “just like a real person,” as Neb said, and they made him drink a few cups of a refreshing infusion whose ingredients were furnished by the vegetable pharmacy of Granite House.

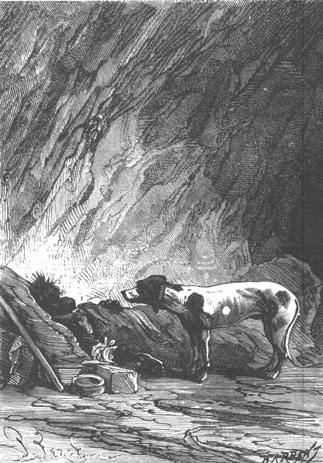

At first Jup’s sleep was agitated, but little by little his breathing became more regular and they let him sleep quietly. From time to time Top came in “on tip toe” so to speak, to visit his friend and he seemed to approve of all the attention that was lavished upon him. One of Jup’s hands hung outside the bed and Top licked it humbly.

Top came to visit his friend.

That same morning they proceeded to bury the dead who were dragged up to the forest of the Far West and interred.

This attack, which might have had serious consequences, was a lesson for the colonists and henceforth they did not go to sleep without one of them being sure that all the bridges were raised and that no invasion was possible.

However Jup, after having given them some serious fears for a few days, made a vigorous comeback. His constitution prevailed, the fever went down little by little and Gideon Spilett, who was something of a doctor, soon considered the difficulty over. On the 16th of August Jup began to eat. Neb made sweet dainty dishes for him which the patient tasted sensually because, if he had a pet fault, it was that he was a bit of a gourmand and Neb had never tried to correct him from this fault.

“What do you want?” he said to Gideon Spilett, who reproached him several times for spoiling him. “He has no other pleasure than that of his mouth, poor Jup, and I am very happy to be able to recognize his services in this way.”

Ten days after having taken to bed, on the 21st of August, Jup got up. His wounds were healed and they could well see that he would not be long in recovering his suppleness and his usual vigor. Like all convalescents, he was then consumed by a devouring hunger and the reporter let him eat whatever his heart desired because he trusted this instinct which is very often lacking in rational beings and which would protect the orang from any excess. Neb was overjoyed to see his pupil’s appetite return.

“Eat, my Jup,” he said to him, “and want for nothing. You have shed your blood for us and the least I can do is to help you recover.”

Finally on the 25th of August they heard Neb calling his companions.

“Mister Cyrus, Mister Gideon, Mister Herbert, Pencroff, come! Come!”

The colonists, gathered in the large hall, got up at the call of Neb, who was then in the room reserved for Jup.

“What is it?” asked the reporter.

“Look!” replied Neb, bursting into laughter.

And what did they see? Master Jup smoking tranquilly and seriously, squatting like a Turk by the door of Granite House.

“My pipe!” shouted Pencroff. “He has taken my pipe! Ah! My brave Jup, I give it to you as a present. Smoke, my friend, smoke!”

And Jup seriously emitted thick puffs of smoke and seemed to be getting unlimited joy.

Cyrus Smith showed no astonishment about this incident and he cited several examples of tame apes who had become familiar with the use of tobacco.

But from this day on, Master Jup had a pipe of his own, the sailor’s ex-pipe, which hung in his room near a supply of tobacco. He filled it himself, lit it with a burning coal and appeared to be the happiest of quadrumanes. One could well believe that this common interest could only tighten the bonds of close friendship that already united the worthy ape and the honest sailor.

“Perhaps he is a man?” Pencroff sometimes said to Neb. “Would it astonish you if one day he spoke to us?”

“My word, no,” replied Neb. “What astonishes me is that he hasn’t already spoken because all he lacks is speech.”

“It would amuse me all the same,” said the sailor, “if one fine day he said to me, ‘suppose we change pipes, Pencroff.’”

“Yes,” replied Neb, “What a pity he was born mute.”

With the month of September the winter was completely over and activities were resumed with zest.

The construction of the boat advanced rapidly. It was already completely decked and structured on the inside so as to bind together all the parts of the hull with a framework made pliable with steam. This would take up the slack of dimensional tolerances.

Since there was no lack of wood, Pencroff proposed to the engineer that they build a double hull on the inside with a watertight inner planking which would completely assure the strength of the boat.

Cyrus Smith, not knowing what the future had in store, approved the sailor’s idea of making the boat as strong as possible.

The inner planking and the bridge of the boat were completely finished around the 15th of September. To caulk the seams, they packed them with dry seaweed, which was hammered in between the planking of the hull, the inner planking and the bridge; then these seams were covered with boiling tar which had been abundantly furnished by the pines of the forest.

The fitting of the boat was very simple. First it was ballasted with heavy pieces of granite cemented in a bed of lime. They stowed away about twelve thousand pounds of this. A deck was placed above this ballast and the interior was divided into two rooms, with two benches extending along its length to serve as chests. The foot of the mast supported the partition which separated the two rooms, with access to the bridge through two hatchways provided with canopies.

Pencroff had no trouble in finding a tree suitable for the mast. He chose a young fir, very straight and without knots, which he squared at the base and rounded at the top. The ironwork for the mast, the rudder and the hull had been crudely but firmly made on the forge at the Chimneys. Finally yards, topmast, boom, spars, oars, etc., all was finished in the first week of October and it was agreed that they would make a trial run of the boat in the coastal waters of the island in order to know how well it took to the sea and to what degree they could depend on it.

During all this time, other work had not been neglected. The corral was rearranged because the flock of sheep and goats counted a certain number of young which had to be lodged and nourished. The colonists did not fail to visit the oyster bed, nor the warren, nor the coal and iron beds, nor several still unexplored parts of the forests of the Far West which were very full of game.

Certain indigenous plants were also discovered and if they did not have any immediate use, they still would contribute to a diversification of the vegetable reserves of Granite House. One was a species of Hottentot’s fig, resembling those of Capetown, with fleshy edible leaves. Another produced seeds which contained a sort of flour.

On the 10th of October, the boat was launched. Pencroff was radiant. The operation succeeded perfectly. The fully rigged boat was pushed on rollers to the edge of the shore and was lifted by the rising tide to the applauds of the colonists, especially Pencroff who showed no modesty on this occasion. Moreover, his vanity would outlast the completion of the boat since, after having constructed it, he would be called upon to command it. The grade of captain was awarded by common agreement.

On the 10th of October, the boat was launched.

To satisfy Captain Pencroff, it was first necessary to give the boat a name and after several proposals discussed at length, the voters agreed on that of Bonadventure which was the baptismal name of the honest sailor.

As soon as the Bonadventure was lifted by the rising tide, they could see that it would be perfectly seaworthy and that it would be easy to navigate at all speeds.

All that was left was to give it a try on that very day, with an excursion off the coast. The weather was beautiful, the breeze fresh and the sea smooth, especially off the southern shore where the wind had already been blowing for an hour.

“Get in! Get in!” shouted Captain Pencroff.

But they had to eat before leaving and it even seemed best to carry some provisions on board in case the excursion was prolonged until evening.

Cyrus Smith was also in a hurry to try out the boat since the plans had originated with him although, on the sailor’s advice, he had often modified some parts; but he did not have as much confidence in it as Pencroff did, and since the latter no longer spoke of the voyage to Tabor Island, Cyrus Smith hoped that the sailor had forgotten it. He was reluctant in fact, to see two or three of his companions venture so far in this small boat which did not displace more than fifteen tons.

At ten thirty everyone was on board, even Jup and Top. Neb and Herbert raised the anchor which was buried in the sand near the mouth of the Mercy, the spanker sail was hoisted, the Lincolnian flag waved at the top of the mast, and the Bonadventure commanded by Pencroff, took to the open sea.

In order to leave Union Bay it was first necessary to sail before the wind and they could see that under this situation the speed of the vessel was satisfactory.

After having doubled Flotsam Point and Cape Claw, Pencroff had to sail close to the wind in order to coast along the southern shore of the island. After navigating by a series of tacks, he saw that the Bonadventure could sail at about five points from the wind and that it could suitably hold itself against the drift. It tacked very well, having “the knack” as the sailors would say, and its tacking even deserved praise.

The passengers of the Bonadventure were truly enchanted. They had here a good boat which could given them good service if need be. With this fine weather and good breeze, the excursion was charming.

Pencroff went out to three or four miles from shore on the way to Port Balloon. The island then appeared in all its development and under a new aspect, with the varied panorama of its shore from Cape Claw to Reptile Promontory, with the nearest part of the forest in which the green conifers stood out from the other trees whose young foliage was barely blooming, and with Mount Franklin, which dominated it all, with white snow at the top.

“It is beautiful,” cried Herbert.

“Yes, our island is beautiful and good,” replied Pencroff. “I love it like I love my poor mother. It received us, poor and lacking everything, and what is lacking now to the five children who fell on it from the sky?”

“Nothing,” replied Neb, “Nothing, Captain!”

And the two worthy gentlemen gave three formidable hurrahs in honor of their island.

During this time, Gideon Spilett, leaning against the mast, was drawing the panorama which developed before his eyes.

Cyrus Smith looked in silence.

“Well, Mister Cyrus,” asked Pencroff, “what do you think of our boat?”

“She seems to conduct herself well,” replied the engineer.

“Good! And do you think that at this time it could undertake a voyage of some duration?”

“What voyage, Pencroff?”

“To Tabor Island, for example.”

“My friend,” replied Cyrus Smith, “I believe that, if need be, we should not hesitate to put our trust in the Bonadventure, even for a longer trip; but as you know, it would pain me to see you leave for Tabor Island since nothing obliges you to go there.”

“Everyone likes to know his neighbors,” replied Pencroff stubbornly. “Tabor Island is our neighbor and it is the only one! Politeness requires that we go there, at least to pay it a visit.”

“The devil,” said Gideon Spilett, “our friend Pencroff is so proper.”

“I am not proper about anything,” retorted the sailor, a bit vexed by the engineer’s opposition but not wishing to cause him any pain.

“Think, Pencroff,” replied Cyrus Smith, “that you cannot go to Tabor Island alone.”

“One companion will be sufficient.”

“So be it,” replied the engineer. “That means that you will risk depriving the Lincoln Island colony of two colonists out of five.”

“Out of six!” replied Pencroff. “You forget Jup.”

“Out of seven!” added Neb. “Top is another worthy member.”

“There is no risk, Mister Cyrus,” replied Pencroff.

“That is possible, Pencroff; but I repeat to you that we will expose ourselves without necessity.”

The stubborn sailor did not reply and dropped the conversation deciding to pick it up again later. But he hardly suspected that an incident would come to help him and to change into an act of humanity what was after all a debatable caprice.

In fact, after having been out at a distance, the Bonadventure approached the shore sailing toward Port Balloon. It was important to note the channels among the banks of sand and reefs so as to put down beacons if need be, since this small inlet would be the boat’s official port.

They were only a half mile from the coast and it was necessary to tack to make headway against the wind. The speed of the Bonadventure was then only moderate because the breeze, partly hindered by the high land, hardly filled the sails, and the sea, smooth as ice, only rippled to an occasional wind.

Herbert had stationed himself up front in order to indicate the route to follow among the channels when all of a sudden he shouted:

“Luff, Pencroff, luff.”

“Luff, Pencroff, luff,” said Herbert.

“What is it?” replied the sailor, getting up. “A rock?”

“No... wait,” said Herbert... “I do not see well... luff again... good ... over a little...”

And saying this Herbert, leaning over the edge, quickly plunged his arms into the water and then got up saying:

“A bottle!”

He held in his hand a closed bottle which he had seized a few cables from shore.

Cyrus Smith took the bottle. Without saying a single word, he smashed the cork and took out a wet paper from which he read these words:

“Castaway... Tabor Island: 153° W. Long.—37° 11′ Lat. S.”