The young convalescent began to get up.

Gideon Spilett took the box and opened it. It contained about two hundred grains of a white powder, a few particles of which he carried to his lips. The extreme bitterness of this substance could not be mistaken. It certainly was the precious alkaloid of Peruvian bark, the pre-eminent anti-periodic.

He had to administer this powder to Herbert without hesitating. How it got there, they would discuss later.

“Some coffee,” said Gideon Spilett.

A few moments later Neb brought over a lukewarm cup of the infusion. Gideon Spilett threw in about eighteen grains1 of quinine and they succeeded in making Herbert drink the mixture.

There was still time because the third attack of the pernicious fever had not manifested itself.

And it may be added, that it must not return!

Besides, it is necessary to say, everyone had recovered hope. The mysterious influence had been exercised anew and in a supreme moment, when they had despaired of it!...

After a few hours Herbert was resting peacefully. The colonists could then discuss this incident. The intervention of the stranger was more evident than ever. But how had he been able to get into Granite House during the night? It was absolutely inexplicable and in truth, the means used by the “genie of the island” were no less strange than the genie himself.

During this day, the sulphate of quinine was administered to Herbert about every three hours.

The next day Herbert experienced a certain improvement. He had not yet recovered and intermittent fevers are subject to frequent and dangerous recurrences but he had no lack of care. And then the specific was there and not far doubtless, was he who brought it! In short, an immense hope returned to everyone’s heart.

This hope was not unjustified. Ten days later, on the 20th of December, Herbert began his convalescence. He was still weak and a severe diet had been imposed on him but there had been no further attack. And then the docile child voluntarily submitted to all the prescriptions which were imposed on him. He yearned to get better.

Pencroff was like a man who had been snatched from the bottom of an abyss. He had crises of joy which bordered on delirium. After the time for the third attack had passed, he seized the reporter in his arms and smothered him. From then on he only called him Doctor Spilett.

It remained to discover the real doctor.

“We will find him,” repeated the sailor.

And certainly the man, whoever he was, could expect a somewhat rugged embrace from worthy Pencroff.

The month of December ended and with it this year of 1867 during which the colonists of Lincoln Island had been so sorely tried. They began the year 1868 with magnificent weather, superb warmth and a tropical temperature which fortunately was cooled by sea breezes. Herbert revived, and from his bed, placed near one of the Granite House windows, he inhaled the wholesome salty air which restored his health. He began to eat and God knows what dainty dishes, frivolous and savory, Neb prepared for him.

“It is enough to make one wish for an illness,” said Pencroff.

During all of this time the convicts had not once shown themselves in the vicinity of Granite House. Of Ayrton there was no news and if the engineer and Herbert still had any hope of finding him again, their companions did not doubt that the unfortunate had succumbed. However these uncertainties could not continue and as soon as the lad would be able bodied, the expedition whose result was so important, would be undertaken. But they would have to wait a month perhaps, because it would take all the forces of the colony to get the upper hand over the convicts.

Besides, Herbert was getting better and better. The congestion of the liver had disappeared and the wounds could be considered as definitely cicatrized.

During the month of January, important work was done at Grand View Plateau; but it consisted only in saving what they could of the devastated harvests of corn and vegetables. The seeds and plants were gathered so as to furnish a new harvest for the coming half-season. As to rebuilding the poultry yard, the mill and the stables, Cyrus Smith preferred to wait. While his companions and he would be in pursuit of the convicts, the latter could well pay a new visit to the plateau and would not fail to give rein to their profession as pillagers and arsonists. They would see about rebuilding when they had purged the island of these scoundrels.

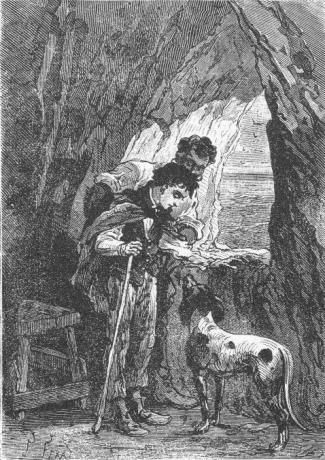

The young convalescent began to get up during the second fortnight of the month of January, first an hour each day, then two, then three. His strength returned visibly, so vigorous was his constitution. He was then eighteen years old. He was tall and promised to become a noble man with a commanding presence. From this time on his convalescence, though still requiring care—and Doctor Spilett showed himself to be very strict—proceeded on schedule.

The young convalescent began to get up.

Toward the end of the month, Herbert had already been to Grand View Plateau and the beach. A few sea baths taken in the company of Pencroff and Neb did him a world of good. Cyrus Smith felt he could already set the day of departure which was fixed for the 15th of February. The nights, which were very clear at this time of the year, would favor the search that they would make of the entire island.

The preparations for this exploration were therefore begun and they had to be considerable because the colonists had sworn that they would not enter Granite House again until their double purpose had been attained: on the one hand, to destroy the convicts and find Ayrton again if he was still alive; on the other, to discover who presided so effectively over the destinies of the colony.

Of Lincoln Island, the colonists were well acquainted with all of the eastern shore from Cape Claw to the Mandible Capes, the vast Tadorns marsh, the neighborhood of Lake Grant, Jacamar Woods between the corral and the Mercy, the courses of the Mercy and Red Creek, and finally the buttresses of Mount Franklin, where they had established the corral.

They had explored, but only in an imperfect way, the vast coastline of Washington Bay from Cape Claw to Reptile Promontory, the forested and marshy west coast and those endless dunes which ended at the mouth of Shark’s Gulf.

But they knew nothing of the large wooded portions which covered Serpentine Peninsula, all of the right bank of the Mercy, the left bank of Falls River, and the network of these buttresses and these entrenchments which supported three quarters of the base of Mount Franklin in the west, the north and the east, there where so many retreats doubtless existed. Consequently several thousand acres of the island had still escaped their investigations.

Hence it was decided that the expedition would be carried across the Far West so as to include all of the part situated on the right bank of the Mercy.

Perhaps it would be best to go first to the corral where they had reason to believe that the convicts had found refuge again either to pillage it or to install themselves there. But either the devastation of the corral was an accomplished fact by now and it was too late to prevent it, or the convicts had entrenched themselves there and there would always be time to go and dislodge them from their retreat.

Thus, after discussion, they held to the original plan, and the colonists resolved to reach Reptile Promontory by going through the woods. They could blaze a trail with the ax and thus beat the first path over a route which would put Granite House in communication with the extremity of the peninsula over a length of sixteen to seventeen miles.

The cart was in perfect condition. The onagers, being well rested, could make a long trip. Provisions, camping equipment, a portable stove and various utensils were loaded into the cart as well as arms and munitions chosen with care from the now complete Granite House arsenal. But they must not forget that the convicts were perhaps roaming the woods and that in these thick forests a gun could quickly be fired and reach its mark. Out there it would be necessary for the small troop of colonists to stay together and not separate for any reason.

It was also decided that no one would remain at Granite House. Top and Jup themselves would take part in the expedition. The inaccessible dwelling could guard itself all alone.

The 14th of February, the day before the departure, was a Sunday. It was devoted entirely to rest and sanctified by thanks addressed to the Creator. Herbert, entirely recovered but still a bit weak, would have a place reserved for him in the cart.

The next day, at dawn, Cyrus Smith took the measures necessary to protect Granite House against any invasion. The ladders which were formerly used for climbing up, were brought to the Chimneys and buried deep in the sand so that they could be used on their return because the drum of the elevator was dismantled and nothing remained of the apparatus.

Pencroff stayed to the last in Granite House to finish this work and he lowered himself by means of a double cord held firmly from below and which once thrown to the ground would allow no communication between the upper landing and the beach.

Pencroff lowered himself by means of a cord.

The weather was magnificent.

“It will be a warm day,” said the reporter joyously.

“Bah, Doctor Spilett,” replied Pencroff, “we will move along sheltered by the trees and we will not even see the sun.”

“Let’s go!” said the engineer.

The cart was waiting on the beach in front of the Chimneys. The reporter saw to it that Herbert took his place there, at least during the early hours of the trip, and the lad yielded to his doctor’s prescriptions.

Neb put himself at the head on the onagers. Cyrus Smith, the reporter and the sailor were in front. Top frisked about joyously. Herbert had offered a place to Jup in his vehicle and Jup accepted without formality. The moment for departure had arrived and the small troop took to the road.

The cart first turned the corner at the river’s mouth then, after having ascended the left bank of the Mercy for a mile, it crossed the bridge at the end of which the route to Port Balloon began. There the explorers left the route on their left and plunged into the cover of these immense woods which formed the region of the Far West.

For the first two miles the well spaced trees allowed the cart to move freely; from time to time they had to chop away at creepers and brushwood but no serious obstacle opposed the passage of the colonists.

The thick branches kept the ground in the cool shade. Deodars, douglas, casuarinas, banksias, gum and dragon trees and other already discovered species succeeded each other as far as the eye could see. All the species of birds usual to the island were found there, grouse, jacamars, pheasant, lories and the entire babbling family of cockatoos, parakeets and parrots. Agouti, kangaroo and capybara ran about the grass, all of which reminded the colonists of the first excursions which were made upon their arrival on the island.

“Nevertheless,” noted Cyrus Smith, “I notice that these animals, quadrupeds and birds, are more fearful than formerly. These woods have been recently scoured by the convicts who must certainly have left traces.”

And, in fact, in many places they recognized the more or less recent passage of a troop of men: here, cuts made on trees, perhaps to mark out the road: there, some cinders from an extinguished fire and some footprints preserved on clay ground. But, in short, nothing seemed to indicate a permanent encampment.

The engineer had suggested to his companions that they refrain from hunting. The noise from the firearms would warn the convicts who were perhaps roaming about the forest. Besides, the hunters would necessarily drift away from the cart and they were severely forbidden to wander alone.

During the second part of the day, about six miles from Granite House, movement became rather difficult. In order to pass certain thickets, they had to chop down some trees to make a road. Before doing that, Cyrus Smith took care to send Top and Jup into the thick underbrush. They accomplished their task conscientiously and when the dog and the orang returned without giving any signal, they knew that there was nothing to fear, neither from the convicts nor from the wild beasts—two sorts of individuals of the genus animal whose ferocious instincts put them on the same level.

During the night of this first day, the colonists camped about nine miles from Granite House on the banks of a small tributary of the Mercy whose existence they were ignorant of. This was a part of the hydrographic system which gave the soil its astonishing fertility.

They ate heartily because the colonists had a very sharp appetite and measures were taken to pass the night without disturbance. If the engineer had had to deal only with ferocious animals, jaguars or others, he would simply have lit a fire around the encampment which would suffice to protect it; but the convicts would more likely be alerted by the flames than frightened by them, and it was best in this case to surround themselves by darkness.

Besides, the watch was strictly organized. Two of the colonists would watch together and it was agreed that every two hours they would wake up their companions. In spite of his protests, Herbert was relieved of the guard. Pencroff and Gideon Spilett on the one hand and the engineer and Neb on the other, took turns in mounting guard to the approaches to the encampment.

Besides, there were only a few hours to the night. The obscurity was due rather to the thickness of the branches than to the disappearance of the sun. The silence was barely troubled by the raucous howls of the jaguars and the derisive laughter of the apes which seemed particularly to irritate Master Jup.

The night passed without incident and the next day, the 16th of February, the journey, more slow than laborious, was resumed through the forest.

The night passed without incident.

They were only able to make six miles on this day because at every instant they had to blaze a trail with the ax. Being true “settlers”, the colonists spared the large and fine trees whose felling would besides have cost them enormous fatigue. They sacrificed the small ones; but the result was that the route hardly followed a straight line and was lengthened by numerous detours.

During this day, Herbert discovered new species which had not been previously seen on the island, such as the tree fern with hanging branches that were shaped like water flowing out of a vase, and the carob whose long pods the onagers nibbled on eagerly and which would furnish a sweetish pulp of excellent taste. There the colonists also found again some magnificent kauri trees, arranged by groups, with cylindrical trunks crowned by a cone of verdure rising to a height of two hundred feet. These were the “king of trees” of New Zealand, as famous as the cedars of Lebanon.

As to the fauna, there were no species that had not been previously recognized by the hunters. However, without getting near, they caught a glimpse of a couple of large birds peculiar to Australia, cassowaries which go under the name of emus, and which are five feet tall and of brown plumage, belonging to the order of grallatory birds. Top dashed after them as fast as his four legs could carry him but the cassowaries easily outdistanced him, such was their speed.

They found a few more traces left by the convicts in the forest. Near a fire which appeared to have been recently extinguished, the colonists noticed footprints which they carefully examined. By measuring each against the others according to their length and width, they easily identified traces of the feet of five men. The five convicts had evidently camped in this area; but—and this was the object of a minute examination—they could not discover a sixth footprint which, in this case would have been Ayrton’s foot.

“Ayrton was not with them!” said Herbert.

“No,” replied Pencroff, “and if he was not with them it is because these wretches have already killed him! But these scoundrels therefore do not have a den where we can go and track them down like tigers!”

“No,” replied the reporter. “It is very likely that they go about at random and it is in their interest to roam around in this way until such time as they become the masters of the island.”

“The masters of the island!” shouted the sailor. “The masters of the island!...” he repeated, and his voice was choked as if an iron collar had seized his throat. Then in a calmer voice:

“Do you know, Mister Cyrus,” he said, “what bullet this is that I have shoved into my weapon?”

“No, Pencroff.”

“It is the bullet that went through Herbert’s chest and I promise you that it will not miss its mark.”

But these justifiable reprisals would not return Ayrton to life and from the examination of the footprints left on the ground they must alas conclude that they could no longer hope to see him alive.

That evening they camped forty miles from Granite House and Cyrus Smith estimated that they were at most five miles from Reptile Promontory.

And in fact, the next day they reached the extremity of the peninsula. The forest had been crossed over its entire length but with no indication which would allow them to discover the retreat where the convicts took refuge nor that of the no less secret sanctuary of the mysterious stranger.