Hebert was thrown to the ground by a savage being.

Pencroff, Herbert, and Gideon Spilett remained silent in the darkness.

Pencroff shouted.

There was no response.

The sailor then struck the flint and lit a twig. For an instant this light illuminated a small room which appeared to be absolutely abandoned. To the rear there was a crude fireplace with a few cold cinders supporting an armful of dry wood. Pencroff threw the burning twig on it, the wood crackled and gave a vivid flame.

The sailor and his two companions then saw an unmade bed, with wet and yellowish covers which proved that it had not been used for a long time; in a corner of the fireplace, two kettles covered with rust and an overturned pot; a wardrobe with a few half mildewy sailor’s clothes; on the table, tin kitchen utensils and a bible rotted by the dampness; in a corner, some tools, a shovel, a pickaxe, a pick, two hunting guns one of which was broken; on a raised platform, a still intact barrel of powder, a barrel of shot and several boxes of primers; all covered with a thick layer of dust which had perhaps accumulated over long years.

“There is no one here,” said the reporter.

“No one,” replied Pencroff.

“It is a long time since this room has been occupied,” Herbert noted.

“Yes, a really long time!” replied the reporter.

“Mister Spilett,” Pencroff then said, “instead of returning on board, I think that it would be best to pass the night in this dwelling.”

“You are right, Pencroff,” replied Gideon Spilett, “and if its owner returns, well! Perhaps he will not be pleased to find the place taken over.”

“He will not return!” said the sailor, shaking his head.

“You believe that he has left the island?” asked the reporter.

“If he has left the island, he would have taken his arms and his tools,” replied Pencroff. “You know the value that castaways attach to these things, which are the last remains from a wreck. No! No!,” repeated the sailor convincingly, “No!, he has not left the island. If he had rescued himself with a boat that he made he would still not have left behind these things of prime necessity. No, he is on the island!”

“Living?...” asked Herbert.

“Living or dead. But if he is dead, I suppose he has not buried himself,” replied Pencroff, “and we will at least find his remains.”

It was then agreed that they would pass the night in the abandoned dwelling. A supply of wood found in a corner provided sufficient warmth. The door closed, Pencroff, Herbert and Gideon Spilett, seated on a bench, stayed there, speaking little and thinking. They were in a frame of mind to imagine anything. While waiting they listened carefully to outside noises. If the door were to suddenly open and if a man should present himself to them, it would not have surprised them in spite of everything that showed the dwelling to be abandoned. Their hands were ready to clasp the hands of this man, this castaway, this unknown friend whose friends were waiting.

But no noise was heard, the door did not open and so the hours passed.

How long this night seemed to the sailor and his two companions! Herbert alone slept for two hours because at his age sleep is a necessity. All three were in a hurry to continue the previous day’s exploration and to search the most secret corners of the islet. The conclusions reached by Pencroff were absolutely justified and it was nearly certain that since the house was abandoned and the tools, utensils and arms were still there, that its host had succumbed. It was therefore agreed to look for his remains and at least give them a Christian burial.

Day appeared. Pencroff and his companions immediately proceeded to examine the dwelling.

It had really been built in a good location atop a small hill on which five or six magnificent gum trees grew. In front, across the trees, a large clearing had been made with the axe, which allowed the view to extend over the sea. A small lawn, surrounded by a wooden fence fallen in ruin, led to the shore with the mouth of the creek to the left.

This dwelling had been constructed of planks and it was easy to see that these planks came from the hull or the bridge of a vessel. It was therefore probable that a disabled ship had been thrown on the coast of the island, that at least one man of the crew had been saved and that by means of the debris from the vessel this man, having tools available, had constructed this dwelling. And this was even more evident when Gideon Spilett, after having gone around the dwelling, saw on a plank—probably one of those which formed the bulwark of the wrecked vessel—these letters already half defaced:

BR.TAN..A

“Britannia!” shouted Pencroff, after the reporter called him. “It is a very common name for vessels but I cannot say if it is English or American.”

“It is of little importance, Pencroff.”

“Of little importance, in fact,” replied the sailor, “and if the crew’s survivor still lives, we will save him regardless of his nationality. But before continuing our exploration, let us return on board the Bonadventure.”

A sort of uneasiness took hold of Pencroff on the subject of his boat. If perchance the islet was inhabited and if some inhabitant took possession... but he shrugged his shoulders at such an unlikely supposition.

Still the sailor was not sorry to go to dine on board. The route, already traced out, was not long, hardly a mile. They got back on the road again, all the while looking carefully at the woods and the underbrush from which the goats and the pigs fled by the hundreds.

Twenty minutes after having left the dwelling, Pencroff and his companions again saw the eastern shore of the island and the Bonadventure, held by its anchor which was buried deep in the sand.

Pencroff could not hold back a sigh of satisfaction. After all, this boat was his child and fathers have the right to be uneasy more often than to be reasonable.

They came on board and dined so that there would be no need to eat again until much later; then, the meal finished, the exploration was resumed with the most minute care.

In short, it was very probable that the sole inhabitant of the islet had succumbed. It was for a dead person rather than a living one that Pencroff and his companions were searching. But their search was in vain and for half a day they looked uselessly among the massive woods that covered the islet. They had to admit that if the castaway was dead, there no longer remained any trace of his body and that doubtless some beast had devoured it down to the last bone.

“We will leave tomorrow at daybreak,” said Pencroff to his two companions who, at about two o’clock in the afternoon, were lying in the shadow of a cluster of pines in order to rest for a few moments.

“I believe that we can take with us, without any scruples, the utensils which belonged to the castaway,” added Herbert.

“I believe that too,” replied Gideon Spilett, “and these arms and tools will complement the materiel of Granite House. If I am not mistaken the supply of powder and shot is considerable.”

“Yes,” replied Pencroff, “but let us not forget to capture one or two couples of these pigs of which Lincoln Island is deprived...”

“Nor to collect these seeds,” added Herbert, “which will give us all the vegetables of the old and new worlds.”

“It would then perhaps be best to stay another day longer on Tabor Island,” said the reporter, “in order to collect everything that can be useful to us.”

“No, Mister Spilett,” replied Pencroff, “I will ask you to leave tomorrow at daybreak. The wind appears to me to have a tendency to change into a westerly and after having had a good wind for coming we will have a good wind for returning.”

“Then let us not lose any time!” said Herbert, getting up.

“Let us not lose any time,” replied Pencroff. “You, Herbert, collect the seeds which you know better than we. During this time, Mister Spilett and I will hunt for some pigs and even in Top’s absence, I dare say that we will succeed in capturing a few.”

Herbert took the footpath that would bring him to the cultivated part of the islet while the sailor and the reporter went directly into the forest.

Many specimens of the pig family fled from them and these animals, oddly agile, did not appear in a humor to be approached. However, after a half hour of pursuit, the hunters succeeded in getting hold of a couple who were hiding in a thick brushwood when some shouting resounded a few hundred feet away in the north of the islet. With these shouts were mingled some horrible hoarse sounds that had nothing human about them. Pencroff and Gideon Spilett stood up and the pigs profited from this movement by escaping just when the sailor was ready to tie them.

“That’s Herbert’s voice!” said the reporter.

“Run!” shouted Pencroff.

And soon the sailor and Gideon Spilett were running as fast as their limbs could carry them to the place where the shouting emanated.

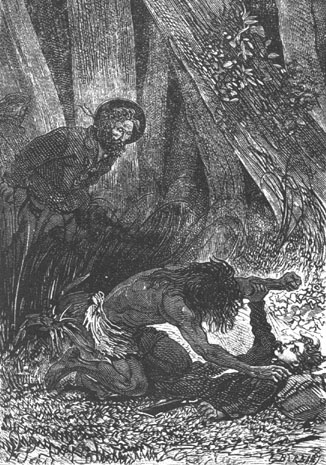

They did well to hurry because, on making a turn in the footpath near a clearing, they saw the lad thrown to the ground by a savage being, a gigantic ape doubtless, who was about to harm him.

Hebert was thrown to the ground by a savage being.

To pounce upon this monster, throw him in turn to the ground, wrench Herbert from him and hold him down firmly was the work of an instant for Pencroff and Gideon Spilett. The sailor had a hurculean strength and the reporter was also robust and, in spite of the monster’s resistance, he was firmly tied down so that he could not move.

“You aren’t hurt, Herbert?” asked Gideon Spilett.

“No! No!”

“Ah! If this ape had hurt you!...” shouted Pencroff.

“But this not an ape!” replied Herbert.

At these words Pencroff and Gideon Spilett looked at this strange being who lay on the ground.

In truth, it was not an ape! It was a human creature. It was a man! But what a man. A savage in all the horrible meaning of the word, and what was even more dreadful was that he seemed to have fallen into the last stages of brutishness.

With a bristling head of hair, an unkempt beard that came down to his chest, an almost nude body except for a rag covering his privates, fierce eyes, enormous hands, long fingernails, skin as dark as mahogany, feet as hard as hoofs, such was the miserable creature that was nevertheless called a man. But they truly had the right to ask themselves if there still was a soul in this body or if the vulgar instinct of the brute alone survived in him.

“Are you sure that this is a man or that he once was that?” Pencroff asked the reporter.

“Alas! There is no doubt of it,” replied the latter.

“Is this then the castaway?” asked Herbert.

“Yes,” replied Gideon Spilett, “but the unfortunate no longer has anything human about him.”

The reporter spoke the truth. It was evident that if the castaway had ever been a civilized being, loneliness had made him a savage and perhaps worse, a veritable man of the woods. Hoarse sounds issued from his throat and from his teeth which had the shrillness of carnivore’s teeth intended for the chewing of raw meat. Memory had abandoned him long ago and it doubtless was a long time since he had used tools, arms, or made a fire. One could see that he was nimble and agile but all the physical faculties had developed in him to the detriment of the moral qualities.

Gideon Spilett spoke to him. He did not seem to understand nor even to hear... And yet, upon looking into his eyes, the reporter felt that all reason was not extinguished within him.

However, the prisoner did not struggle nor did he try to break his bonds. Was he crushed by the presence of these men whose fellows he had once been? Did some fleeting memory of humanity return to a corner of his brain? If freed would he try to escape or would he remain? They did not know but they did not make the test and after having looked the wretched person over carefully:

“Whatever he is,” said Gideon Spilett, “and whatever he has been and whatever will become of him, it is our duty to take him with us to Lincoln Island.”

“Yes! Yes!” replied Herbert, “and perhaps, with attention, we will be able to awaken some glimmer of intelligence in him.”

“The soul is not dead,” said the reporter, “and it will be a great satisfaction to save this creature of God from brutishness.”

Pencroff shook his head doubtfully.

“We ought to try it in any case,” replied the reporter. “Humanity requires it of us.”

It was, in fact, their duty as civilized beings and Christians. The three of them understood this and they well knew that Cyrus Smith would approve of their action.

“Shall we keep him tied?” asked the sailor.

“Perhaps he will walk if we free his feet,” said Herbert.

“Let us try,” replied Pencroff.

The prisoner’s feet were freed but his hands remained firmly bound. He got up by himself but showed no desire to escape. His dry eyes darted a sharp look at the three men who walked beside him but nothing showed that he remembered that he was their fellow being or at least that he once was so. A hiss continued to escape from his lips. He looked fierce but he did not resist.

At the reporter’s suggestion, they brought the unfortunate to his dwelling. Perhaps the sight of those objects which belonged to him would make some impression on him. Perhaps it would act as a spark to revive his obscure thought, to illuminate his extinct soul.

The dwelling was not far. In a few minutes they all arrived there; but once there the prisoner recognized nothing and it seemed that he had lost awareness of all these things.

All they could say about this degree of brutishness was that his imprisonment on the islet was already of long duration and after having arrived there a rational person, loneliness had reduced him to this state.

The reporter then had the idea that the sight of fire might produce some reaction in him and in an instant one of the beautiful flames that even attract animals was lit in the fireplace.

The sight of the flame at first seemed to attract the attention of the unfortunate; but he soon drew back and his unconscious look turned elsewhere.

Evidently there was nothing more to do for the moment at least, except to return on board the Bonadventure, and that being done, he remained there in Pencroff’s custody.

Herbert and Gideon Spilett went back to the islet to finish their operations and a few hours later they returned to the shore carrying utensils and arms, a collection of vegetable seeds, some game and two couples of pigs. All went on board and the Bonadventure was made ready to raise anchor as soon as the next morning’s rising tide would be felt.

The prisoner had been placed in the forward cabin where he calmly remained, silent, insensible and mute.

Pencroff offered him food but he pushed away the cooked meat that was presented to him and which doubtless no longer suited him. And in fact, when the sailor showed him one of the ducks that Herbert had killed, he threw himself upon it like a beast and devoured it.

“You think he will recover?” asked Pencroff, shaking his head.

“Perhaps,” said the reporter, “it is not impossible that our attention will produce a reaction in him because it is loneliness that has make him what he is and henceforth he will no longer be alone.”

“It has doubtless been a long time that the poor man has been in this state,” said Herbert.

“Perhaps,” replied Gideon Spilett.

“How old could he be?” asked the lad.

“That is difficult to say,” replied the reporter, “because it is impossible to see his features under the thick beard which covers his face, but he is no longer young and I suppose he is at least fifty years old.”

“Have you noticed, Mister Spilett, how deeply set his eyes are?” asked the lad.

“Yes, Herbert, and I will add that they are more human than we had a right to expect from his appearance.”

“Well, we will see,” replied Pencroff, “and I am curious to know what Mister Smith will think of our savage. We went in search of a human creature and will return with a monster. Well, we did what we could.”

The night passed and they did not know whether or not the prisoner slept, but in any event, since he had been bound he did not stir. He was like a beast first overpowered by capture but who would go into a rage later.

At daybreak the next day—the 15th of October—the change in weather predicted by Pencroff took place. The wind, blowing northwest, favored the return of the Bonadventure; but at the same time it was a fresh breeze which would make navigation more difficult.

Anchor was weighed at five o’clock in the morning. Pencroff took in a reef in his large sail and put the bow to east northeast to sail directly toward Lincoln Island.

The first day’s passage was not marked by any incident. The prisoner remained calm in the forward cabin and since he had been a sailor, it seemed that the motion of the sea produced a beneficial reaction in him. Did some memory of his former calling come back to him? In any case he remained calm, astonished rather than dejected.

The next day—the 16th of October—the wind blew much stronger and more from the north, and consequently from a direction less favorable to the Bonadventure which bounced on the waves. Pencroff soon sailed close to the wind and without saying anything, he began to become uneasy at the condition of the sea which foamed violently against the front of his boat. Certainly if the wind did not change it would take longer to reach Lincoln Island than it did to get to Tabor Island.

In fact on the morning of the 17th it was forty eight hours since the Bonadventure had left and nothing indicated that they were near the island. Moreover, it was impossible to determine where they were or to estimate it because the direction and the speed had been very irregular.

Twenty four hours later, there was still no land in sight. The wind was then directly ahead and the sea wretched. They had to quickly maneuver the sails of the boat which the waves of the sea covered in wide areas, taking in the reefs and often changing the tack. It even happened, on the 18th, that the Bonadventure was completely laid aback by a wave and if the passengers had not taken the precaution in advance of tying themselves to the bridge they would have been carried away.

On this occasion, Pencroff and his companions were very occupied in disentangling themselves. They received an unexpected assistance from the prisoner who ran up the hatchway, as if his sailor’s instinct had gained the upper hand, and broke an awning using a spar in order to allow for the quicker escape of the water which filled the bridge; then the boat disencumbered, he went down to his room without saying a word.

Pencroff, Gideon Spilett and Herbert, absolutely astonished, let him proceed.

However the situation was bad and the sailor had reason to believe that they were lost on this immense sea without any possibility of getting back on the track.

The night of the 18th to the 19th was dark and cold. However, around eleven o’clock the wind became calm, the surging fell and the Bonadventure, being less jolted, acquired a greater speed. It performed well.

Neither Pencroff, nor Gideon Spilett, nor Herbert thought of taking an hour’s sleep. They watched carefully because Lincoln Island could not be far off. By daybreak they would not know where the current and wind had carried the Bonadventure and it would be almost impossible to rectify its direction.

Pencroff, uneasy to the last degree, did not despair however, because he had a well tempered spirit. Seated at the helm, he searched obstinately, endeavoring to pierce the darkness which enveloped him.

About two o’clock in the morning he suddenly got up:

“A fire! A fire!” he shouted.

“A fire! A fire!” shouted Pencroff.

And in fact, a vivid flame appeared about twenty miles to the northeast. Lincoln Island was there and this flame, evidently lit by Cyrus Smith, showed the route to follow.

Pencroff, sailing too much to the north, altered his direction and put his bow toward this fire which burned above the horizon like a star of the first magnitude.