Cyrus Smith put his hand on his shoulder.

The next day—the 20th of October—at seven o’clock in the morning, after a voyage of four days, the Bonadventure gently went aground on the beach at the mouth of the Mercy.

Cyrus Smith and Neb, very uneasy about the bad weather and the prolonged absence of their companions, had climbed to Grand View Plateau at daybreak and they finally saw the boat which had been so long in returning.

“God be praised! There they are!” shouted Cyrus Smith.

Neb, in his joy, began to dance, turning around, clapping his hands and shouting: “Oh! My master,” a pantomime more touching than the finest discourse.

The engineer’s first thought, on counting the people that he could see on the bridge of the Bonadventure, was that Pencroff had not found the castaway of Tabor Island or that at least the unfortunate had refused to leave his island to exchange his prison for another.

And indeed, Pencroff, Gideon Spilett and Herbert were alone on the bridge of the Bonadventure.

At the moment when the boat came alongside, the engineer and Neb were waiting on the shore and before the passengers could jump to the sand, Cyrus Smith said to them:

“We have been very uneasy at your delay, my friends. Have you met with any difficulty?”

“No,” replied Gideon Spilett, “on the contrary, everything went well. We will tell you about it.”

“However,” replied the engineer, “you have failed in your search, since there are only three of you, the same as when you left.”

“Excuse me, Mister Cyrus,” replied the sailor, “we are four!”

“You found this castaway?”

“Yes.”

“And you brought him back?”

“Yes.”

“Living?”

“Yes.”

“Where is he? What is he?”

“He is,” replied the reporter, “or rather he was a man. That Cyrus, is all that we can tell you.”

The engineer was soon brought up to date on what had occurred on the trip. They related under what conditions the search had been conducted, how the only dwelling on the islet had long been abandoned, how finally the capture was made of a castaway who no longer seemed to belong to the human species.

“And the point is,” added Pencroff, “that I don’t know if we were right in bringing him here.”

“Certainly you were right, Pencroff,” replied the engineer vividly.

“But this unfortunate no longer has his reason.”

“That is possible for now,” replied Cyrus Smith, “but hardly several months ago this unfortunate was a man like you or me. And who knows what will become of the last survivor among us after a long solitude on this island? It is a misfortune to be alone, my friends, and it seems that loneliness has quickly destroyed his sanity since you found this poor soul in such a condition.”

“But, Mister Cyrus,” asked Herbert, “what leads you to believe that the brutishness of this unfortunate occurred only a few months ago?”

“Because the document that we found has been recently written,” replied the engineer, “and only the castaway could have written this document.”

“Assuming,” said Gideon Spilett, “that it was not composed by a companion of this man, since dead.”

“That is impossible, my dear Spilett.”

“Why?” asked the reporter.

“Because the document would have mentioned two castaways,” replied Cyrus Smith, “but it only spoke of one.”

In a few words, Herbert related the incidents that occurred during the return crossing and emphasized the strange fact about the fleeting return of the prisoner’s senses when, for a moment, he became a sailor again at the height of the storm.

“Well, Herbert,” replied the engineer, “you are right to attach a great importance to this fact. This unfortunate is not incurable and it is despair that has made him what he is. But here he has his fellow beings and since he still has a soul within him, this soul we will save.”

The castaway of Tabor Island, to the great pity of the engineer and to the great astonishment of Neb, was then escorted from the forward cabin that he occupied on the Bonadventure, and once on land his first impulse was to flee.

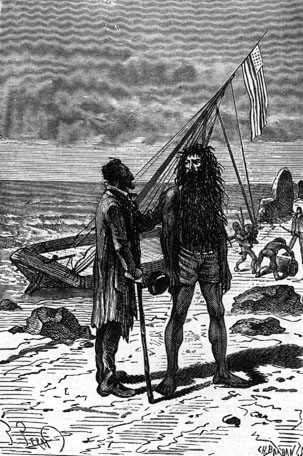

But Cyrus Smith approached, put his hand on his shoulder with a gesture full of authority, and looked at him with infinite gentleness. Soon the unfortunate submitted to his authority, he became calmer little by little, his eyes lowered, his face inclined and he made no more resistance.

Cyrus Smith put his hand on his shoulder.

“This poor forsaken man!” murmured the engineer.

Cyrus Smith looked at him carefully. Judging from his appearance, the castaway no longer had anything human about him but Cyrus Smith detected an elusive glimmer of intelligence, as had the reporter previously.

It was decided that the castaway, or rather the stranger—because this is what his new companions would henceforth call him—would remain in one of the rooms of Granite House from which, besides, he could not escape. They escorted him there without difficulty and with good care they could hope that one day he would become an additional companion to the colonists of Lincoln Island.

The reporter, Herbert and Pencroff were dying of hunger. During a breakfast that Neb quickly put together, they told Cyrus Smith all the incidents in detail that marked the exploration of the islet. He agreed with his friends on this point that the stranger had to be either English or American because the name Britannia suggested this, and besides, under his unkempt beard, under this hairy growth, the engineer thought that he saw the characteristic features of the Anglo-Saxon.

“But, as a matter of fact,” said Gideon Spilett to Herbert, “you did not tell us how you met this savage and all we know is that he would have strangled you if we did not chance to arrive in time to save you.”

“Dear me,” replied Herbert, “I’m not sure what happened. I was, I believe, occupied with collecting some plants when I heard a noise like an avalanche falling from a tree. I hardly had time to turn around... The unfortunate was doubtless hiding in a tree and fell upon me in less time than I can tell you about it and without Mister Spilett and Pencroff...”

“My child!” said Cyrus Smith, “you ran a real danger, but without it perhaps this poor person would always have remained hidden and we would not have had an additional companion.”

“You hope then, Cyrus, to rehabilitate him?” asked the reporter.

“Yes,” replied the engineer.

The meal ended, Cyrus Smith and his companions left Granite House and returned to the beach. They then unloaded the Bonadventure. The engineer examined the arms and the tools but he saw nothing that would enable him to establish the identity of the stranger.

The capture of the pigs was considered a very profitable thing for Lincoln Island and these animals were conducted to the stables where they easily became acclimatized.

The two barrels containing powder and shot, as well as the primer caps, were very well received. They agreed to establish a small arsenal either outside Granite House or even in the upper cavern where there was no fear of the effects of an explosion. Nevertheless the use of pyroxle would be continued because this substance gave excellent results and there was no reason to substitute ordinary powder for it.

When the unloading of the boat was completed:

“Mister Cyrus,” said Pencroff, “I think that it would be prudent to put our Bonadventure in a secure place.”

“Isn’t the mouth of the Mercy suitable?” asked Cyrus Smith.

“No, Mister Cyrus,” replied the sailor. “Half the time it is stranded on the sand which strains it. It is a good boat, as you can see, and it behaved well during the windstorm that struck us so violently on our return,”

“Can’t we leave it afloat on the river?”

“Doubtless, Mister Cyrus, we could do that, but this mouth presents no shelter, and with the winds from the east, I believe that the Bonadventure would suffer much from the sea.”

“Well, where would you like to put it, Pencroff?”

“At Port Balloon,” replied the sailor. “This small creek, protected by the rocks, seems to me to be just the port we need.”

“Isn’t it a little far?”

“Bah! It’s not more than three miles from Granite House, and we have a fine straight road to take us there.”

“Do it, Pencroff. Bring your Bonadventure there,” replied the engineer. “And yet I would much prefer to have it under our more immediate surveillance. When we have the time, we must make a small port for it.”

“Wonderful,” shouted Pencroff. “A port with a lighthouse, a breakwater and a repair dock. Ah, really, with you Mister Cyrus, everything becomes easy.”

“Yes, my worthy Pencroff,” replied the engineer, “but on the condition, however, that you help me because you are good for three quarters of all our work.”

Herbert and the sailor then went back on board the Bonadventure, the anchor was raised, the sail hoisted, and the wind rapidly brought it to Cape Claw. Two hours later it was resting on the tranquil waters of Port Balloon.

During the first days that the stranger passed at Granite House, did he give them reason to think that his savage nature was changing? Did some intense spark shine deep within his obscure mind? Would the soul return to the body? Yes, assuredly, and on this very point, Cyrus Smith and the reporter asked themselves whether the sanity of the unfortunate had ever been totally extinct.

Since he was accustomed to the wide open spaces and unlimited liberty which he enjoyed on Tabor Island, the stranger at first manifested some muted fury and they feared that he would throw himself on the beach from one of the windows of Granite House. But little by little he became calm and they were able to allow him the liberty of his movements.

They then had good reason for hope. Already forgetting his instincts as a raw flesh eater, the stranger accepted a less bestial nourishment than that which he ate on the islet. Cooked meat did not produce the revulsion in him that he had manifested on board the Bonadventure.

Cyrus Smith profited from a moment when he was asleep to cut his hair and unkempt beard which had formed a sort of mane and gave him a savage appearance. He also dressed him in more suitable clothes after having removed the rag which covered him. Thanks to these cares, the result was that the stranger presented a human figure and it even seemed that his eyes became more gentle. Certainly, when his former intelligence would return, the figure of this man would have a sort of beauty.

Each day Cyrus Smith imposed upon himself the task of spending a few hours in his company. He worked near him and occupied himself with various things so as to capture his attention. In fact, a spark would suffice to illuminate his soul, some remembrance crossing his mind would bring back his sanity. They had seen this on board the Bonadventure during the storm.

The engineer did not neglect to speak loudly so as to penetrate at the same time the organs of hearing and sight to the depths of his dulled intelligence. Sometimes one of his companions, sometimes another, sometimes all would join him. Very often they spoke of those things that would interest a sailor and which would appeal to him. At times the stranger paid some attention to what was said and the colonists soon concluded that he partly understood them. Sometimes his expression was deeply painful, proving that he suffered inwardly, because his face could not be mistaken about this, but he did not speak in spite of some moments when they thought he had some words at the tip of his tongue.

Be it as it may, the poor soul was calm and sad. But was his calm only apparent? Wasn’t his sadness only the consequence of his being confined? They could not tell. Seeing only certain objects in a limited field and having no contact except with the colonists to whom he became accustomed, having no desire to satisfy, having better food and better clothing, it was natural that his physical nature should change a bit; but did this signify a new life for him or rather, to use a word which would correctly apply to him, was he merely becoming tame like an animal with a master? This was an important question that Cyrus Smith wanted to resolve quickly yet he did not wish to hurt his patient. For him the stranger was a patient. Would he ever become a convalescent?

The engineer observed him constantly. How he was on the alert for his soul to show itself, if one may speak this way! How he was ready to seize it!

With sincere emotion the colonists followed all the phases of this cure undertaken by Cyrus Smith. They also helped him with this work of humanity and all, except perhaps for the incredulous Pencroff, soon began to share his hope and his faith.

The stranger’s calm was deep, as has been said, and he showed a sort of attachment to the engineer, to whose influence he visibly submitted. Cyrus Smith decided to test this by bringing him to other surroundings, before this ocean which he formerly gazed at and to the edge of the forest which would remind him of those forests where he spent many years of his life.

“But,” said Gideon Spilett, “can we hope that once set at liberty he will not escape?”

“That’s an experiment we must make,” replied the engineer.

“Good!” said Pencroff. “When this here chap finds the open spaces in front of him and he inhales the fresh air, he will be off as fast as his legs can carry him.”

“I don’t believe that,” replied Cyrus Smith.

“Let us try,” said Gideon Spilett.

“Let us try,” replied the engineer.

This day was the 30th of October and consequently it was now nine days that the castaway from Tabor Island had been a prisoner at Granite House. It was warm and a fine sun cast its rays on the island.

Cyrus Smith and Pencroff went to the room occupied by the stranger and found him leaning at the window looking at the sky.

“Come, my friend,” the engineer said to him.

The stranger immediately got up. With his eyes fixed on Cyrus Smith, he followed him. The sailor was to the rear of him, having little confidence in the result of the experiment.

Arriving at the door, Cyrus Smith and Pencroff made him take his place in the elevator while Neb, Herbert and Gideon Spilett waited for them below at the foot of Granite House. The basket descended and in a few moments all were together on the shore. The colonists moved away a little from the stranger so as to give him some liberty.

The latter took a few steps advancing toward the sea. His gaze shone with extreme animation but he did not seek to escape. He looked at the small waves which, broken by the islet, came to die on the sand.

“This is still only the sea,” noted Gideon Spilett, “and it is possible that it does not inspire him with the desire to escape.”

“Yes,” replied Cyrus Smith, “we must take him to the plateau, to the edge of the forest. There the experiment will be more conclusive.”

“Besides, he cannot escape,” noted Neb, “since the bridges are raised.”

“Oh!” said Pencroff, “a man like this will not be inconvenienced by a creek such as Glycerin Creek. He will cross it in a single bound.”

“We will see,” Cyrus Smith was content to reply, not taking his eyes away from those of his patient.

The latter was taken to the mouth of the Mercy, and they all then ascended the left bank of the river, reaching Grand View Plateau.

Arriving in the vicinity of the first fine trees of the forest, with the breeze gently blowing through their foliage, the stranger inhaled with rapture the scent that permeated the air and a deep sigh escaped from his chest.

A deep sigh escaped from his chest.

The colonists kept to the rear ready to seize him if he should try to escape.

And in fact, he was on the point of throwing himself into the creek that separated him from the forest and for a moment his legs bent like a spring... But almost immediately he fell back, he collapsed and large tears flowed from his eyes.

“Ah!” said Cyrus Smith, “you have become a man again, since you are crying.”